Bacon Moore: Flesh and Bone

at the Ashmolean, Oxford.

The pairing of two great artists of the 20th century made this exhibition powerful, thought- provoking and intense, and it made me rethink both artists. Moore, predominantly a sculptor, Bacon, a painter who was greatly influenced by sculpture and particularly the work of Rodin, were both engaged in the depiction, the re-invention of the human body. Both artists lived through two World Wars and having experienced the Blitz, undertook to restore the human body to a kind of dignified resignation in the face of suffering and isolation. Each undertook this in his own way, Moore through his belief in humanism while Bacon's world-view was predominantly nihilistic. The work of each artist presents the human condition as isolated in his or her secular environment which is increasingly characterised by atrocities perpetrated by human beings to one another. Moore believed that the artist had a responsibility to society, while Bacon did not.

Moore's figures have dignity, resulting in peace, a resignation to the cycle of life and death while acknowledging the horrors that human beings experienced in the 20th century - his sculptures are timeless, eternal, tranquil, monumental, expressing a permanency, nobility, a sense of human resilience. Bacon's paintings are expressions of a transitory state, moments of desperation, a scream in the face of the isolation, pain, horror and catastrophes of life: his figures are deformed, convulsed, exaggerated, distorted, fractured forms, fragmented

'like some sort of cubism which instead of angles and planes uses scooped, circling, spiralling brushstrokes loaded with fleshy pigment'. (Review in the Times).

The work of both artists reflects their lives: Moore, happily married, an established figure whose work has featured in countless public spaces. Bacon, a solitary man, an outsider.

'The intensity with which Bacon can express revulsion for flesh and the ignoble aspects of man is emphasised by Moore's monumentalising of the human form so that it expresses the permanency of landscape shapes. Tranquil, solid and confident of their supremacy over fleeting and destructive emotions, his figures embody the spirit of eternity, while Bacon's embody transitory states and mortality. Both sides of the coin need to be shown'. (from Marlborough New London Gallery catalogue, 1964).

Henry Moore:

'Within the dehumanising circumstances of modern life, a completely human art must do far more than create figures which are traditional or anatomically correct. The artist who is himself an intensely vital, energetic and energizing man has to establish and realise and uphold his individuality against the environment. In order to do this he has to absorb into himself some of the machine-like, beyond-the-human-scale characteristics of the age. A mother and child, or a reclining figure, or the most primitive of figures, have to absorb into themselves the strength of machines, whereby they can fortify their own humanity. This is what Moore does in his sculpture'. (Stephen Spender, 1979).

Three Piece Reclining Figure No. 2: Bridge Prop, 1963 (bronze)

one more view

Standing Nude, 1924, (pen and ink)

Two Standing Figures, 1940 (pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper)

Figure in a Shelter, 1941 (pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, chalk, watercolour, wash, pen and ink on paper)

Shelter Drawing: Three Fates, 1941 (pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, wash, pen and ink on paper)

Group of Seated Figures, 1941 (pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, gouache, pen and ink on paper)

Four Studies of Miners at the Coalface, 1942, (pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour, wash, pen and ink on paper).

'A great deal can still be done with three-dimensional form as a means of expressing what people feel about themselves, and about nature, and about the world around them. But I don't think that we shall or should, ever get far away from the thing that all sculpture is based on, in the end,: the human body' (Moore, 1961)

Mask, 1929 (cast concrete)

Composition, 1931 (blue Hornton stone)

Three Points, 1939-40, (cast iron, unique)

The Helmet, 1939-40, (bronze)

Three Standing Figures, 1945, (plaster with surface colour)

Openwork Head no. 2, 1950 (bronze)

Three Upright Motives, 1955, (bronze)

Seated Figure on Ledge, 1957, (bronze)

'This is perhaps, what makes me interested in bones as much as in flesh, because the bone is the inner structure of all living form. It's the bone that pushes out from inside... And so the knee, the shoulder, the skull, the forehead, the part where from inside you get a sense of pressure of the bone outwards - these for me are the key points'. (Moore)

Fragment Figure, 1957, (bronze)

Three Quarter Figure: Lines, 1980 (plaster)

Francis Bacon:

'The paintings make horrifying statements with very great force. They are by an observer so profoundly affected by the kind of life he observes that, although protesting, they seem corrupted by corruption. After Bacon most other contemporary painting seems decoration, doodling, aestheticism or stupidity. His work (is) extremely devoid of pleasure, perhaps this is partly due to the life of disillusionment he leads, which he faces in its implications; perhaps it is the old English puritanism and dislike of pleasure cropping up again'. (Stephen Spender, 1962).

'Bacon represents by an extraordinary and baffling process and it is here that the strength and mystery of his art lies... It reverses every familiar pictorial sequence: it is the opposite of traditional painting... He doesn't offer an essence of an appearance but the opposite, whatever that might be: something like a pile of clinker from which the essence has long since been burned out'. (Andrew Forge, The New Statesman).

Studio Interior, 1936, (pastel on paper)

Man Kneeling in Grass, 1952 (oil on canvas)

Study for Portrait III, (After the Life-Mask of William Blake), 1955, (oil on canvas)

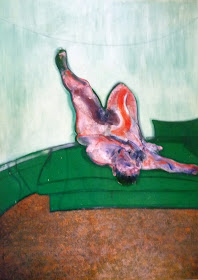

Lying Figure, 1959, (oil on canvas)

'Painting is the pattern of one's own nervous system being projected on the canvas'. (Bacon)

Two Figures in a Room, 1959, (oil on canvas)

Head of a Man, 1959, (oil on canvas)

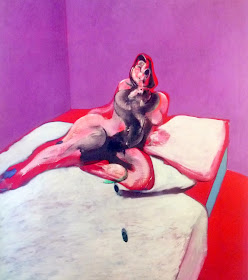

Seated Figure, 1962, (oil on canvas)

Portrait of Man with Glasses III, 1963, (oil on canvas).

'My ambition would be to do something really beautiful and not ugly as all my paintings are, before I die'. (Bacon)

Two Studies from the Human Body, 1975, (oil on canvas)

Two Figures, 1975, (oil on canvas)

Untitled (Kneeling Figure), 1982

I found this exhibition very useful in that it helped me clarify my feelings about Bacon's work. His work leaves me uneasy and disturbed, a feeling that lingers long after I have stopped looking at his paintings. Intellectually I understand the reasons for and the power of the distorted, convulsed bodies that writhe. At the same time, I admire and marvel at the sculptural quality of his figures: I can think of no painter that has achieved this to such an effect. Similarly, I love the colours in his paintings, they give me a warm, 'safe' feeling, a glow, and what a contradiction this is to the effect the contorted figures have on me. Such a mixed response, attesting to the power of the work. The verdict? My feelings about Bacon are unchanged: unease, feeling disturbed, troubled, wanting to walk away. But, a more profound understanding.

Juxtapositions:

'...They are at extreme poles and there is grandeur in the contrast between them: Moore's timelessness, his authoritative, silent, female warmth, the acrid masculinity of Bacon's images, counting their minutes. It is like a vast resume of what art can encompass. But the affinities between them are just as meaningful. What more precious lesson about the sources of art than in the example of their commitment to their subject-matter? Certain affections, obsessively held, regulate everything they do. They stalk their internal quarries implacably. They seem to be familiar with their own innermost recesses, to understand without anxiety the connection between their fantasies and the forms they can make with their hands'. (Andrew Forge, New Statesman).

'The intensity with which Bacon can express revulsion for flesh and the ignoble aspects of man is emphasised by Moore's monumentalising of the human form so that it expresses the permanency of landscape shapes. Tranquil, solid and confident of their supremacy over fleeting and destructive emotions, his figures embody the spirit of eternity, while Bacon's embody transitory states and mortality. Both sides of the coin need to be shown'. (from Marlborough New London Gallery catalogue, 1964).

Moore, Reclining Figure: Festival, 1951 (bronze)

Bacon, Lying Figure in a Mirror, 1971, (oil on canvas)

* * *

Moore, King and Queen, 1952-53, (bronze)

Inspired by a hieratic Egyptian sculpture in the British Museum.

Bacon, Study from Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1965, (oil on canvas)

* * *

Moore, Falling Warrior, 1056-57, (bronze)

Bacon, Portrait of Henrietta Moraes, 1963, (oil on canvas)

* * *

Bacon, Second Version of Triptych, 1944, 1988 (oil and alkyds on canvas)

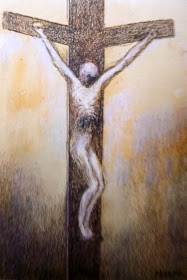

'... Several figures raised on structures ... and there would probably be a pavement raised high out of its naturalistic setting, out of which they could move as though out of pools of flesh rose the images, if possible, of people walking on their daily round. I hope to be able to do figures arising out of their own flesh with their bowler hats and umbrellas and make them figures as poignant as a Crucifixion'. (Bacon)

Moore, Crucifixion I, 1982 (charcoal, wax crayon, watercolour, chinagraph, pencil, ballpoint pen on paper)

Moore, Crucifixion II, 1982, (pencil, charcoal, wax crayon, watercolour wash, pastel wash, chinagraph, ballpoint pen on paper)

Moore, Crucifixion III, 1982 (wax crayon, charcoal, pencil, watercolour wash, ink wash on paper)

* * *

Moore, Square Reclining Forms, 1961-2 (sketchbook)

Bacon, Composition, 1933 (gouache on paper)

Source:

Bacon Moore: Flesh and Bone, an Ashmolean publication.

More on Henry Moore:

http://a-place-called-space.blogspot.co.uk/2012/03/henry-moore-at-leamington-art-gallery.html

http://a-place-called-space.blogspot.co.uk/2011/10/henry-moore-at-ysp.html

More on Francis Bacon:

http://a-place-called-space.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/bacon-and-rodin-in-dialogue.html

http://a-place-called-space.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/francis-bacons-studio.html