Nature Study by Louise Bourgeois

at Compton Verney.

The flaming trees were a nice surprise as we parked our car

On the way to the gallery, as we were walking in the grounds we came across The Couple by Louise Bourgeois (2007-2009) (aluminium)Like many of Bourgeois' sculptures, The Couple possesses both human and organic characteristics as the central figures merge together in a vine-like mass. This coiled form relates to the spiral, an important recurring motif within the artist's work, which she associated with the endless cycles of life and nature, and the tightening and release of conflicting emotions. Suspended, the sculpture rotates in the air, its highly polished finish suggesting fluidity and motion whilst reflecting the foliage of the surrounding trees.

Couples first appeared in Bourgeois' drawings in the 1940s but it was not until the 1990s that this motif found expression in her sculpture. The idea relates to the artist's life-long fear of abandonment, as well as familial relationships, sexuality and the body, death and the unconscious.

We soon arrived at the house, but before going in to see the exhibition we wanted to walk around the grounds

Bourgeois' preoccupation with the spider spans her career, but the subject had a particular immediacy for her from the mid-1990s, when she began to make the sculptures for which she is now best known. She connected the spider with her mother, Josephine, who was an accomplished tapestry restorer: 'My best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat and useful as an araignee (spider)'.

Spiders repair their webs and protect their young, yet they are also predators. Bourgeois' monumental bronze sculptures are dominating and somewhat threatening. These associations reflect Bourgeois' mixed view of motherhood; for her, the mother figure has the capacity to be ferocious and powerful, as well as tender the nurturing.

To see more of Bourgeois' spiders you can go here

We then took the stairs to the first floor to see the exhibition. By the door to the exhibition room was Orange Peel Figure, 1998, (orange peel)

Next to Orange Peel Figure was a video by Waldemar Januszczak, showing Bourgeois peeling an orange and reenacting a crude joke that her father used to make at family dinners, which she found deeply humiliating. Bourgeois had a difficult relationship with her father, and the evening meal was often fraught. As she explained: 'What frightened me was that at the dinner table, my father would go on and on, showing off, aggrandizing himself. And the more he showed off, the smaller we felt. Suddenly there was terrific tension'.

The Materiality of Memory:

Louise Bourgeois was born on Christmas Day 1911 in Paris, into a prosperous middle-class family of tapestry restorers. Despite her family's comfortable circumstances, Bourgeois' childhood was the source of traumatic episodes which had a profound impact on her, including her mother's death in 1932 and her father's long-running affair with her English governess.

Bourgeois' primary motivation for making art was to address the emotions and anxieties arising from her early experiences. As she explained: 'my work is really based on the elimination of fears'. Bourgeois' use of different materials was closely linked to her desire to explore a range of different emotions arising from her early memories.

As the works in this part of the exhibition demonstrate, the artist used unconventional materials including sandpaper, textiles and animal bones to communicate her subjects.

This small work on sandpaper looks like a crudely drawn plaque. It can be interpreted as a form of self-portrait. The text refers to the town of Antony, a suburb of Paris, where Bourgeois' family resided and ran a tapestry restoration atelier. In French, 'Fille Mere' was the term for an unmarried mother who, in early 20th century Catholic France, could be cast out of her family home. As well as conveying this general narrative of abandonment and expulsion, the work also expresses the artist's own experiences. Bourgeous described herself as a 'runaway girl'. In 1938 she left France after marrying the American art historian Robert Goldwater and built a new life in New York. She remained there for the rest of her life.

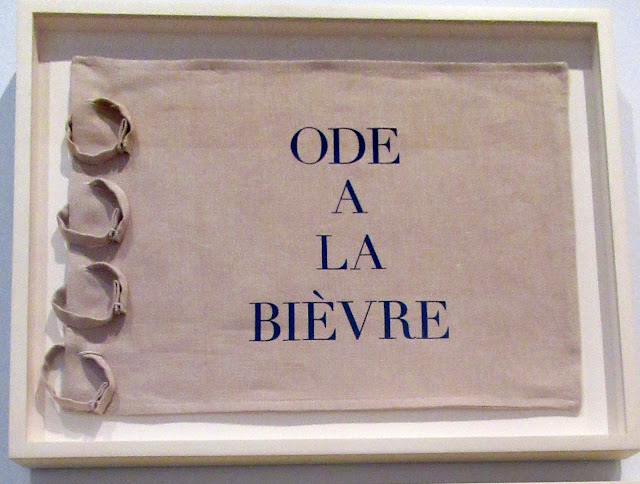

Ode a la Bievre recalls Bourgeois' memories of her childhood home: in 1919, her family moved to the outskirts of Paris, near the Bievre river. In this work she pays homage to the Bievre, which was important to her family's tapestry restoration workshop since it was rich in tannin, an ingredient that enhances the dyeing of fabric. Returning later in life, she found that the river that was once so important to her had been buried by civic planners: 'Only the trees that my father had planted along its edge remained as a witness'. This is an editioned copy of one of two fabric books Bourgeois made from clothing and materials collected over her lifetime, which included towels from her bridal trousseau and garments that she had once worn.

Describing the spiral in relation to her childhood memories, Bourgeois said: 'The spiral is important to me. It is a twist. As a child, after washing the tapestries in the river, I would turn and twist... to wring the water out. Later I would dream of getting rid of my father's mistress. I would do it in my dreams by wriging her neck. The spiral ... represents control and freedom'. Discovering her father's infidelities - for years he had affair with Bourgeois' live-in governmess - was a particularly traumatic moment of betrayal.

Spirals in Bourgeois' work also symbolise the continual cycles of life and nature. This suite of prints was made using traditional Japanese printmaking methods. The grain of the woodblocks used to make the prints gives a unique texture to each sheet and emphasises the connection to the natural world.

Untitled, 1996, (fabric, rubber, steel, wax, bone)

At the age of 84, Bourgeois made this sculpture using clothes and undergarments that she had worn during her lifetime. The composition alludes to the ageing body. Clothing started to appear more frequently in Bourgeois' art in the mid-1990s. Speeaking of its significance as a reminder of identity and past experiences she said: '... you can retell and remember your life by the shape, the weight, the colour, the smell of clothes in your closet'.

Some are filled from within, evoking the body that once wore them.

Hanging alongside these clothes are bones and lumpy or droopping soft forms resembling body parts.

Anthropomorphic Landscapes:

In the 1960s Bourgeois began making sculptures with ambiguous, organic forms, marking a shift in her practice. She regarded these sculptures - like the one displayed below - as anthromorphic landscapes, representing both natural formations and the human body explaining: 'They are anthropomorphic and they are landscape also, since our body could be considered form a topographical point-of-view, as a land with mounds and valleys and caves and holes'.

After the death of her father in 1951 Bourgeois began an engagement with psychoanalysis which would last for many years. This had a profound effect on her art, resulting in a new visual vocabulary. The works on paper displayed below demonstrate how the concept of the anthropomorphic landscape was also expressed in the artist's paintings and drawings, giving form to her anxieties and emotions.

With a cluster of undulating mounds rising to highly polished plateaus, this bronze sculpture resembles a mountainous landscape. However, like many of Bourgeois' biomorphic sculptures, its smooth curves and crevices also evoke the human body, and the title highlights the artist's interest psychoanalysis and the unconscious mind.

The work demonstrates the shift in Bourgeois' sculpture away from the upright, rigid totems of the 1940s and 50s towards more organic, fluid forms suggestive of body parts. This was made during a period when she actively experimented with different techniques and materials including latex, plaster and marble. Although this sculpture is made of bronze, its form suggests fluidity and motion, reminding us that norhing is ever totally fixed.

Bourgeois' concept of the anthromoporphic landscape is clearly expressed in this gouache diptych. At first glance, the composition appears to suggest a river meandering through a landscape. On closer inspection, however, the undulating forms become a cluster of breasts. Breasts appear frequently in her work, symbolising motherhood and the nourishment of children, as well as eroticism and sexuality.

Bourgeois' use of colour was sparing and considered. She often used red, the colour of blood and aggression, to signify the intensity of human emotions. Here it reinforces the bodily aspect of the work.

Untitled, 2004, (watercolour, gouache and pencil on paper)

Bourgeois' use of colour was sparing and considered. She often used red, the colour of blood and aggression, to signify the intensity of human emotions. Here it reinforces the bodily aspect of the work.

Untitled, 2004, (watercolour, gouache and pencil on paper)

Hands and Holding:

Hands appear frequently in Bourgeois' work, symbolising the offering or withholding of support, as well as dependency and the nature of human relationships. The artist's interest in this idea is connected to her lifelong fear of abandonment and isolation, stemming from her mother's death and her father's absences and affairs.

As the works in this part of the exhibition demonstrate, the idea of support is often closely linked to the spiral motif in Bourgeois' work. Arms and outstretched hands weave around one-another, reaching out to offer assistance, an open palm, holding a female figure, emerges from a tight coil of bronze, and stuffed fabric figures hang entwined in mid-air in an ambiguous embrace.

As the works in this part of the exhibition demonstrate, the idea of support is often closely linked to the spiral motif in Bourgeois' work. Arms and outstretched hands weave around one-another, reaching out to offer assistance, an open palm, holding a female figure, emerges from a tight coil of bronze, and stuffed fabric figures hang entwined in mid-air in an ambiguous embrace.

Bourgeois used one of her blouses, as well as socks and tights, to create this stuffed fabric work. Couple I addresses the often complex relationship between men and women. The gender of the headless figures is signified by the (masculine) pinstripe and (feminine) lace collar, their entwined bodies convey ideas about the physical and emotional connection between the sexes rather than the intellectual aspect of a relationship. Suspended from a hook, the couple are bound together in an endless embrace that could suggest tenderness, dependency or domination. Couples in Bourgeois' works are often equated with the fear of abandonment and loss as well as the need for love.

Give or Take, 2002, (bronze, silver nitrate patina)

Bourgeois made this sculpture by casting the forarms and hands of her assistant, Jerry Gorovoy. The two met in 1980 and remained close friends until Bourgeois' death in 2010. Corovoy often modelled for Bourgeois, particularly for works freaturing hands. As the title makes cleaer, this work depicts two gestures.

The open hand offers support, whereas the closed hand withholds contact. Rather than show an interaction between two bodies, the artist has brought these gestures together in one form, suggesting the conflicted feelings that people can experience within themselves. For Bourgeois, human nature was complex and often contradictory.

This work brings trogether the motif of the spiral with the figure of a falling woman, cradled in a cupped hand. The figure's long hair is woven back into a spiral creating a cyclical composition, an image of endless continuity that loops around again and again.

10am is When You Come to Me, 2006, (etchings with watercolour, pencil and gouache on paper, suite of 20)

In this work, Bourgeois traced her hands and those of her assistant, Jerry Gorovoy, to create a portrait of both their working relationship and friendship. The title refers to the daily time of his arrival at the artist's home, reflecting the reliability and familiarity of their shared routine.

second strip of paintings

Dualities:

Bourgeois' art never unquestionably represents one thing or another. The works below highlight some of the dualities her work deals with. Some blur the perceived lines between genders, possessing both male and female attributes, whilst others relate to conflicting impulses which are universal, such as the desire for solitude versus the need for community.

Femme, 2007, (gouache on paper)

Untitled, 2004, (drypoint on fabric)

The Underground Life of Fear, 2003, (etching with watercolour and ink on paper)

Bourgeois grappled with anxiety throughout her life, and the nature of fear was a major theme which she explored in her art. She described fear as: 'Muscling in, at yout temple... the invisible world... like a wood-worm, it drills through your brain....'

She felt that she could address and control her fears by giving them physical form in her art. In this work, fear takes on a biomorphic form reminiscent of a sinuous root system, or the brain's interconnecting neural pathrays. The title conveys the ubiquitous presence of fear, always lurking beneath the surface and threatening to rise up.

She felt that she could address and control her fears by giving them physical form in her art. In this work, fear takes on a biomorphic form reminiscent of a sinuous root system, or the brain's interconnecting neural pathrays. The title conveys the ubiquitous presence of fear, always lurking beneath the surface and threatening to rise up.

This work is an early manifestation of the spiral motif in sculpture. For Bourgeois, the spiral had the capacity to move in two directions, winding inward to represent the desire to retreat, or expanding outwards to open up.

Bourgeois was 97 years of age when she made this monumental work on paper. At that point in her life, she was interested in working on a large scale, creating art that would envelop and overwhelm the viewer. The title is suggesting that she was thinking about the passing years and her own mortality.

Each sheet contains abstract and figurative elements, with meandering lines suggesting red rivers or arteries cycling around images of childbirth, floating figures and shapes resembling organs and body parts. A L'Intini blurs the lines between printmaking, painting and drawing, as Bourgeois layered gouache washes and marks in pencil on top of ething.

Release:

Release:

The works in this final section demonstrate some of the ways in which Bourgeois used forms related to the human body to express extremes of emotion and highlight the relationship between psychological and physical states. Contorted bodies, gaping mouths and long flowing hair appear throughout the artist's work, often signifying emotional release, but their use is often deliberately ambiguous, hinting at the fine line that separates human emotions.

When she asrrived in New York in 1938, Bourgeois was primarily a painter. This composition is one of many she made during her first decade in the city, which she found exhilarating and inspiring, commenting: 'Even though I am French, I cannot think of one of these pictures being painted in France. Every one of them is American'.

The figure in the foreground represents the artist, her wide-open mouth suggesting a moment of intense emotional release, a suggestion which is reinforced by the long hair flowing in the wind. The three small abstract forms in the back ground, emerging from the top of the chimneystack, reference Bourgeois' three sons and the domestic realm.

Triptych for the Red Room, 1994, (aquating, drypoint and engraving on paper)

Arching bodies appear in several works by Bourgeois. Here, we see three pairs of figures, one with male characteristics and one with female. Their gaping mouths and wide eyes suggest a form of release, but its nature is ambiguous, is it paint or ecstasy?

* * *

After seeing the exhibition we moved on to the permanent collection as we wanted to see a portrait of Bourgeois

In the permanent collection we also found this sculpture by Bourgeois:

Bourgeois identified this sculpture as a self-portrait. The sculpture has both male and female sexual characteristics, with multiple prominent breasts and a phallus between its legs, which she related to her role as a mother and guardian of her family: 'the phallus is a subject of my tenderness. After all, I lived with four men. I was the protector'.

Nature Study also calls to mind the hybrid beasts of classical mythology, imagery which the artist would have become familiar with whilst helping to restore Medieval and Renaissance tapestries in her family's workshop as a young girl. In particular, the canine features recall the legend of the founding of Rome and the twin brothers Romulus and Remus who were cared for by a she-wolf after being left in the wilderness.

No comments:

Post a Comment