Surrealism Beyond Borders

at Tate Modern.

There are images commonly associated with Surrealism, a revolutionary cultural movement that prioritised the unconscious and dreams, over the familiar and everyday. Sparked in Paris around 1924, Surrealism has inspired and united artists ever since. This exhibition traces its wide, interconnected impact. It moves away from a Paris-centred viewpoint to shed light on Surrealism's significane around the world from the 1920s to the 1970s. It includes artists who embraced this spirit of revolt and those who shared Surrealist ideas and values but never joined a group. It features some who are intersected with Surrealism at various points - working in parallel, associated loosely or for a short period, or counted in by other Surrealists.

Surrealism is a shifting term, but at its core, it is an interrogation of political and social systems, conventions and dominant ideologies. Inherently dynamic, it has travelled from place to place and time to time - and continues to do so today. Its scope has always been transnational, spreading beyond national borders and defying nationalist definitions, while also addressing specific and local contexts. In a world defined by territorial control - and the consequential ideological constraint, expansionist conflict, and exploitative colonialism - Surrealism has demanded liberation and served artists as a tool in the struggle for political, social and personal freedoms.

Revolution is a central idea for Surrealism, as it offers the possibility for transformation and liberation. Since its conception, Surrealism has challenged predominant systems of power and privilege, division and exclusion, and has been emboldened by a growing chorus of voices. Alongside the cultural and sociopolitical forces that etermined its own evolving history over the last century, Surrealism has presented a model for political engagement and agitation for artists, many of whom have been arrested for 'subversive' behavious.

While Surrealists have expressed revolutionary ideas in poetic and artistic terms, some have also generated collective actions. They have condemned imperialism, racism, authoritarianism, fascism, capitalism, greed, militarism and other forms of power and control. From student, civil rights and anti-war protests, to the decolonisation movement, Surrealism has served as a tool but not a formula.

In the months before the outbreak of WWII, with European nationalism on the rise, Surrealists in Cairo for instance, came together to form a vocal resistance. The group issued a manifesto in 1938 written by Georges Heneim, Long Live Degenerate Art, which references the Nazis' denunciation of modernist art as 'degenerate' and in conflict with their fascist ideology. Strongly critical of conservatism and the ongoing colonial British presence in Egypt, they aligned themselves with 'revolutionary, independent' art liberated from state interference, traditional values and dominant ideologies. In this they responded to ideas articulated in the 1938 manifesto Towards a Revolutionary Art, drafted by Andre Breton and Leon Trotsky at the Mexico City, home of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. It called for an international front in defence of atistic freedom.

In Mexico City, as in other locations, taking up Surrealism meant grappling with the dual forces of internationalism and nationalism. Mexican Muralism and Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Jose Clemente Orozco's grand narrative murals had taken on an official government role since the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). During the 1930s, however, many artists distanced themselves from muralism and, along with Frida Kahlo, forged connections with Surrealism. With its open-door policy, Mexico was a welcoming home to those fleeing totalitarian Europe. Including the political revolutionary Leon Trotsky, the circles around Kahlo and Rivera were internationalist, and it was through their encouragement that many Surrealists arrived in Mexico City. A core community of Surrealist artists who came together in Mexico City were women. In the particular case of Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, their friendship involved the study of Mexico's indigenous cultures and archaeological sites. Influenced by occult and alchemical sources, these artists also infused Surrealism with fejinism, magic and natural forces.

The artworks assembled here reveal some, but certainly not all, of the many routes into and through Surrealism. It challenges conventional accounts that centre Surrealism in Europe, presenting an interrelated network of activity - one that makes visible many lives, locations and encounters linked through the freedom and possibility offered by Surrealism.

Marcel Jean, (France), 1941, Surrealist Wardrobe, (oil paint on wood panel)

Jean's Surrealist work imagines a portal to freedom, his vision projected on the closed doors of a wardrobe.

Dorothea Tanning, (USA), Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (A Little Night Music), 1943, (oil paint on canvas)

This has always been my favourite Surrealist painting. A girl and lifelike doll share the landing and staircase of a hotel with a giant sunflower. Their tattered clothes and the state of the oversized plant suggest the aftermath of a nightmarish struggle. The unknown threat may have been resisted, although the powerful force drawing the girl's hair up appears very active.

Salvador Dali, (Spain), Telephone-Homard, (Telephone Lobster), 1938, (steel, plaster, rubber, resin and paper)

Uniting a working Bakelite telephone with a plaster lobster, Dali made a modern communication device dysfunctional and dangerous, yet playful. The lobster's tail, where its sexual organs are located, is placed directly over the phone's mouthpiece.

Joyce Mansour, (France), Untitled (Object Mechant), Untitled (Nasty Object), 1965-60, (assorte scrapts of metal)

Mansour published her first book of poems in Cairo in 1953. She was 25. Her work caught the attention of the Paris Surrealists and she became central to the group after settling there in 1956. Inspired by Surrealism's unbounded approach to self-expression, that could lead to many different outputs, she produced artworks like this object mechant, a sponge ball into which she pushed nails and bits of metal.

Marcel Duchamp, (France), Why Not Sneeze Rose Selavy? 1921, (wood, metal marble, cuttlefish bone, thermometer and glass)

Duchamp, who participated in Surrealism as a curator and organiser, also showed in Surrealist exhibitions. Duchamp identified this as an 'assisted readymade', as it combines found elements (such as the cage) with his subtle interventions; in this case playing on the visual similarity between sugar cubes and marble blocks.

Pablo Picasso, (Spain), Composition au Gant, (Composition with Glove), 1930, (cardboard, plaster, wood and sand)

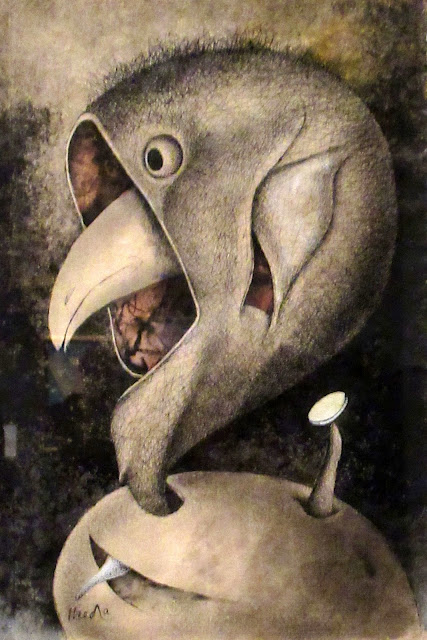

Ikeda Tatsuo, (Japan), Kijuu-ki Bangai: Masuku Dori (Birds and Beasts Chronicle, an Extra Edition, Mask Bird), 1958, (pen, conte and watercolour on paper)

Ikeda turned to art as a way to bear witness to Japan's military defeat during WWII, the Allied Occupation of Japan and nuclear atrocities. Following his art education in Tokyo, he joined a loose collective of artists led by Taro Okamoto. They rejected both abstraction and social realism (art depicting working class experience) as inadequate modes for representing the realities of the post-war period.

Max Ernst, (Germany, France), Deux Enfants sont Menaces par un Rossignol, (Two Children are Threatned by a Nightingale), 1924, (oil paint with painted wood elements and cut-and-pasted printed paper on wood)

With a combination of painted and sculpted elements, and a poetic title, Ernst achieved a dreamlike atmosphere. By tapping into unconscious imagery, this work suggests a strange and anxious narrative. Aligning closely with Surrealist practice, it was soon recognised as a pivotal work.

Surrealism has questioned - and sometimes attempted to overthrow - the strongholds of consciousness and control. Dreams are critical to this end because, like hallucinations and delusions, many have believed that they can reveal the workings of the unconscious mind. In some works featured in this exhibition, fantastical juxtapositions or nighmarish subjects capture the sense of the ordinary made unfamiliar. Surrealist artists in various locations have seized this potential for liberation. They seek the inspiration of dreams to break from limitations imposed by societal customs, or to bring the self, community or work of art beyond the reach of waking reality.

Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams provided an early, vital stimulus for many artists' approaches to Surrealism. Max Ernst's painting, for example, draws upon such an experience: a 'fever vision' in which he saw forms appear in the graining of wood panelling.

Rita Kernn-Larsen, (Denmark), Phantoms, 1934, (oil paint on cardboard)

Kernn-Larsen's exploration of unexpected imagery extended, at times, to a contrast of stylistic modes within a single composition. Phantoms was triggered by the shock of witnessing a drowning at sea, and the image evokes the haunting figures of the victims.

Tarsila do Armaral, (Brazil), Cicada (La Rua), (City) (The Street), 1929, (oil paint on canvas)

Tarsila (as she is known) explained that this painting recorded 'a dream that demanded expression' in Paris.

Yves Tanguy, (France), Milles Fois, 1933

The threatening atmosphere of this painting may reflect the bleak economic and political climate of Europe in the 1930s.

Erna Rosenstein, (Remburg, Austria-Hungary [present day Lviv, Ukraine]), Screens, 2004

Rosenstein travelled from Krakow to Paris in 1938 and saw the Exposition Internationale du Surrealisme. It had a major impact on her work, although she later rejected affiliation with the movement. A survivor of the Holocaust, she processed her traumatic experience through the lens of Surrealism as a catharctic release. Screens features the disembodied heads of her murdered parents. 'The screen for projecting thought', she once said, 'has been there for a long time, it is painting'.

A close look at this jumble of pastel-coloured forms reveals social tumult, political extremism and violence. Mayo had already made connections with the Paris Surrealists in the 1920s. This work dates from his period in Cairo where he exhibited with the group al-Fann wa-I-Hurriya, (Art and Liberty). As the title suggests, this work records one of the frequent confrontations of the period between police and people (including students and labour unions) protesting the treatment of people experiencing poverty and the lingering influence of colonial Britain, despite Egypt's official independence.

Miro made this painting during the final years of Franco's dictatorship in Spain. Its title and date demonstrate the artist's support for the student uprisings of 1968, during which protesters spray-painted Surrealist slogans on the walls of the Sorbonne in Paris. Within this energetic composition that mimics graffiti, the artist added his handprints, connecting himself to their cause. Involved in Surrealism since the early 1920s, Miro later recalled the 'sense of drama and expectation in equal measure [in] that unforgettable rebellion of youth'.

Pablo Picasso, Les Trois Dansenses, 1975, (oil on canvas)

Cossette Zeno, (Dominican Republic), No Use to Talk about the Little Wig, 1952, (oil on canvas board)

This Surrealist portrait wryly mocks male vanity, with its witty title and references to hair in the painting. Zeno countered the conservative teachings of the Universidad de Puerto Rico with a series of humorous compositions with feminist messages.

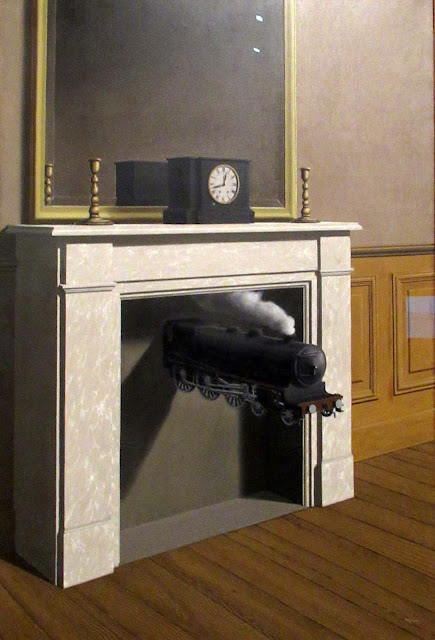

Rene Magritte, (Belgium), Time Transfixed, 1938, (oil on canvas)

Magritte focused on 'elective' affinities' - obscure associations he perceived between objects. He explained: 'I decided to paint the image of a locomotive. In order for its mystery to be evoked, another immediately familiar image without mystery - the image of a dining room fireplace - was joined'.

Claude Cahun, (France), Self-Portrait, 1954

Lee Miller, (USA), Portrait of Space

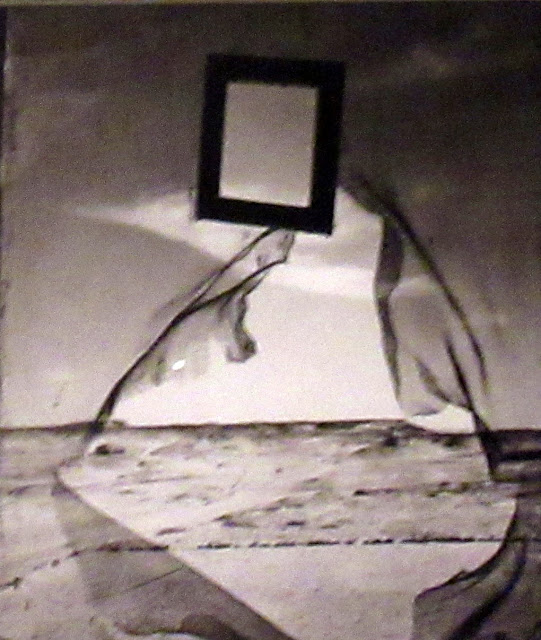

In Portrait of Space, Miller Captures the desert landscape from behind a damaged fly screen. She contrasts interior and exterior spaces in one frame, reflecting the Surrealist's interest in pushing beyond the conscious mind to focus on the unconscious and dreams.

Lee Miller, (USA)

Izquierdo joined a tight community of women Surrealists who convened in Mexico during WWII. Her still life assembles foods associated with the Day of the Dead: green squash used to make calabaza candles and sugar-coated bread.

Leonora Carrington, (UK, Mexico), Self-Portrait, 1937-38, (oil on canvas)

Carrington's Self-Portrait draws on her interest in alchemy, the tarot and Celtic folklore. Here she is sitting with a rocking horse on a hyena, while the horse galloping outside represents the Celtic goddess of fertility and freedom. This self-portrait also reflects her response to gender stereotypes. Looking back, Carrington commented about her role in Surrealism, 'I didn't have time to be anyone's muse'.

No comments:

Post a Comment