This exhibition presents the work of black artists born tetbeween 1887 and 1965 who spent their lives and forged their careers in the American South. While large number of black people had travelled to the northern states between 1910 and 1970 to escape racism, povery and segregation - a movement known as the Great Migration - these artists remained. Their careers were rooted in local communities from South Carolina to the Mississippi River Delta, and from isolated rural areas such as Gee's Bend, Alabama, to urban centres including Atlanta, Memphis and Miami.

With their works, these artists confronted the harrowing history of enslaved African Americans, whose forced labour shaped the economic, social and agrarian culture of the deep South, as well as depicting everyday realities of economic inequality and oppression, social marginalisation and racial conflict. They drew their inspiration from daily life, the local environment, historical and current events, religion, music and the African traditions their had inherited and studied.

Not only are these concerns reflected in the subjects of their works, but they are also implicit in the materials used. The artists often incorporated scrap materials and objects such as tree branches and roots, as well as clay and sand into their works to create some of the most imaginative and powerful paintings, sculptures, quilts and assemblages of the 20th century. Without access to formal art education or traditional galleries, many artists were taught by family members or friends, and often displayed their work on their spacious front porches, on abandoned storefronts or in their own yards.

This is an exhibition about slavery and the scars of that collective trauma run deep through many of the works in the exhibition. Thornton Dial in Blue Skies: The Birds that Didn't Learn How to Fly, where cloth rags hang limp from rubber-coated copper wire, paints a picture of abjection: Mary T Smith's We All Want a Jobe, positions a line of blurred faces beside the desperate, scrawled text of the title to create a tableau haunted by otherness. Ronald Lockett's Oklahoma, made in 1995 in response to the Oklahoma City bombing, pieces together sheets of metal, tin, wire and nails on wood to conjure the horror of murderous white supremacy.

At times the exhibition feels overwhelmingly bleak. And yet, in the material inventiveness of the works and in the sense of meaning made in community, with what materials are available, a powerful counterpoint to suffering emerges. It speaks to resilience, innovation and a propensity for survival - it is life affirming.

Thornton Dial, Cotton Field, 1996, (graphite, charcoal and watercolour on paper)

Most of the artists were connected by close familiar relations and friendships in the American South. Lonnie Holley, who had been working as a gravedigger an cotton picker, began sculpting in 1979, when he carved grave markets for a young niece and nephew following their tragic deaths in a fire. Through a former girlfriend he met Thornton Dial, who had worked in farming and as a steelworker before he became an artist.

Dial founded an artistic dynasty, mentoring two of his sons, Thornton Jr and Richard, as well as his cousin Ronald Lockett. He was also friends with quiltmakers living in Gee's Bend. Unsurprisingly, one may detect certain parallels between the formats and geometric patterns displayed in their works and in Dial's and Lockett's assemblages.

Old cans are transformed into a cosmic night sky and a spray paint can and a piece of old carpet turn into an almost human presence that dances in the centre of this assemblage.

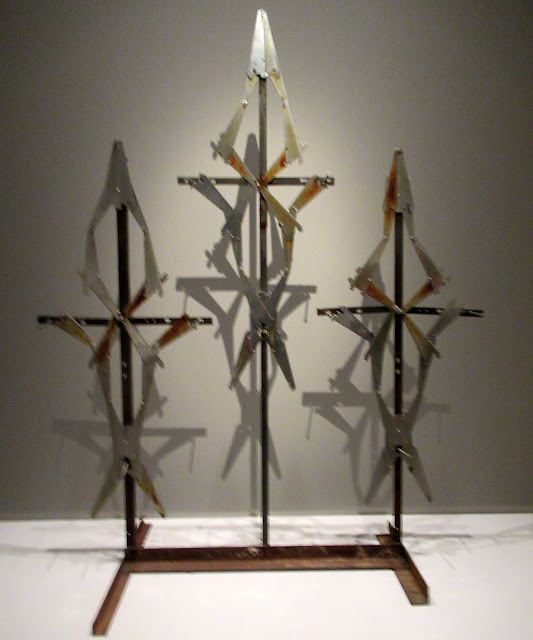

Ronald Lockett, Oklahoma, 1995, (found sheet metal, tin, wire, paint and nails and wood)

A floral tribute to his great-grandmother's back yard made out of tin cans and car paint that exactly resembles the patches on the quilts she used to make. His rusted metal grille, concealing a sinister white mass, is a memorial to the 1995 Oklahoma bombing.

Mary Lee Bendolph, Burgle Boys, 2007, (cotton and polyester)

A poignant masterpiee: these birds are just scraps of black cloth suspended from wire against the canvas, each with curiously human overtones: a glove, a hat, the actual traces of people - beyond the allusions to Jim Crow laws and southern lynchings the tragic poetry is irreducible. These flightless birds have neither life nor freedom.

Richard Dial, Which Prayer Ended Slavery, 1988, (welded steel wire and paint)

looking closer

Lonnie Holley, Keeping a Record of It, (Harmful Music), 1986, (salvaged photograph top, phonograph record and animal skull)

It's like Living in Hell

Lonnie Holley, The Pain that Broke Me, 1995, (window frame and found materials)

Lonnie Holley, Spirit of the Man by the Chicken House Door, 1984, (wooden chair, door, metal can, padlock))

Lonnie Holley, Carrying the Lighter Child, 1986, (enamel on wood)

Joe Light, My Main Man, 1988, (enamel on Masonite)

Archie Byron, Anatomy I, 1987, (sawdust-and-glue relief on wood, with wood frame)

Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Atlanta, 1988, (mud, paint and pigment on wood)

Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Africa, 1980s, (mud, blackberry juice, grass stain and white pigment on wood)

Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Caines Ridge Church, 1986, (mud, grass stain, berry juice, pencil and paint on wood)

Bessie Harvey, Untitled, 1987, (tree root, salvaged wood plank, paste jewels, marbles, modelling paste and paint)

Jesse Aaron, Untitled, 1972, (wood, hat and plastic eyes)

Nellie Mae Rowe, Pocketbook, 1982, (paint and pencil on paper)

Mose Tolliver, Mary, 1986, (house paint on wood)

Sam Doyle, LeBe, 1970s (paint on tin)

Ralph Griffin, Midnight, 1978, (found wood, tin, nails, plastic and paint)

Rowe was a domestic servant in Georgia who taught herself to draw and decorated her yard with images, which were eventually shown in Black Folk Art 1930-80 in Washington in 1976. The purse was made a few years later after Rowe was diagnosed with terminal cancer at the age of 81. It is a celebration of a vital object, apparently empty but treasured: simple as the image itself.

Nellie Mae Rowe, Woman Wearing A Fish Hat, 1980, (acrylic and graphite on wood)

James 'Son Ford' Thomas, Untitled, 1985, (unfired clay, human pair and paint)

James 'Son Ford' Thomas, Untitled

James 'Son Ford' Thomas, Untitled, 1985, (unfired clay, wig, glass marbles, wire, beads and paint)

Charlie Lucas, Three-Way Bicycle, 1985, (bicycle wheels, metal machine parts and electrical wiring)

Yard shows:

These are large-scale, site-specific art installations constructed in the surroundings of domestic properties were first created in the 19th century, and are a distnctively Southern phenomenon.

Joe Minter's African Village in America is one of the last great yard shows standing. Charlie Lucas, who had wanted to be an artist since childhood, also built a sculpture garden on his Alabama farm where he displays his large-scale works in the fields. His sculptures often show humanoid figures made of found mechanical parts.

Miami-based artist Purvis Young took the yard show to the streets of his neighbourhood Overtown, where he displayed his works on the facades of abandoned buildings. His scenes are populated by wild horses, warriors, angels, pregnant women, boats and prison bars, all referring to Young's deep engagement with the struggles and concerns of black people in America.

No comments:

Post a Comment