Guernica (1937) by Pablo Picasso, at the Centro de Arte Reina Sofia.

This is what I managed to glimpse of Guernica.

I have come across this phenomenon twice before: the Mona Lisa by Leonardo Da Vinci at the Louvres in Paris; and the Night Watch by Rembrandt at the Rijksmuseum (you can see that here )

Guernica was inspired by an act of war, the bombing of a Basque town during the Spanish Civil War. The destruction of Guernica was carried out by German aircraft, manned by German pilots, at the request of the Spanish Nationalist commander, General Emilio Mola. Because the Republican government of Spain had granted autonomy to the Basques, Guernica was the capital city of an independent republic. Its razing was taken up by the world press, beginning with The Times in London, as the arch-symbol of Fascist barbarity. Thus Picasso's painting shared the exemplary fame of the event, becoming as well known a memorial of catastrophe as Tennyson's Charge of the Light Brigade had been eighty years before.

Guernica is the most powerful invective against violence in modern art. The weeping woman, the horse, the bull - become receptables for extreme sensation. As John Berger has remarked, Picasso could imagine more suffering in a horse's head than Rubens normally put into a whole crucifixion. The spike tongues, the rolling eyes, the frantic splayed toes and fingers, the necks arched in spasm: these would be unendurable if their tension were not braced against the broken, but visible, order of the painting.

This is a general meditation on suffering, and its symbols are archaic, not historical: the gored and speared horse (the Spanish Republic), the bull (Franco) louring over the bereaved, shrieking woman, the paraphernalia of pre-modernist images like the broken sword, the surviving flower and the dove.

Apart from the Cubist style, the only specificallhy modern elements in Guernica are the eye of the electric light, and the suggestion that the horse's body is made of parallel lines of newsprint, like the newspaper in Picasso's collages a quarter of a century before. Otherwise its heroic abstraction and monumentalised pain hardly seem to belong to the time of photography. Yet, they do: Picasso's most effective way of locating them in that time was to paint Guernica entirely in black, white and grey, so that despite its huge size it retains something of the grainy, ephemeral look one associates with the front page of a newspaper.

Guernica was the last great history-painting. It was also the last modern painting of major importance that took its subject from politics with the intention of changing the way large numbers of people thought and felt about power.

* * *

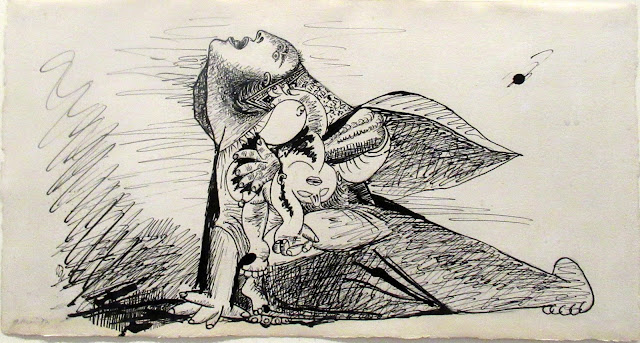

Hanging on the wall across from Guernica were some preparatory sketches for the painting:

Dora Maar, Photo Report of the Evolution of Guernica, 1937

* * *

Hanging on the wall across from Guernica were some preparatory sketches for the painting:

No comments:

Post a Comment