at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

I saw this exhibition a while ago. It presented 22 contemporary artists from across the African diaspora whose work foregrounds the black figure.

The exhibition took as its starting point the idea of race as both a scientific fiction and a lived reality. It considered how artists depict the black form with nuance and depth in a social context in which the black body is often distorted or made invisible in Western imagery. Against this backdrop, these artists have shifted the focus of the representation of blackness from the external and objectified to the subjective and the psychological. Through their work in figuration they invite a shift in the dominant art historical perspective, from 'looking at' the black figure, to 'seeing from' the viewpoint of black artists and the figures they depict.

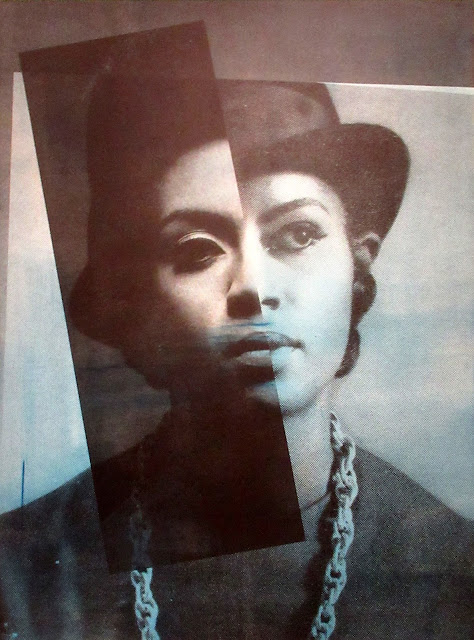

Lorna Simpson, Blue Tulip, 2023, (ink and screenprint on gessoed fibreglass).

Blue Tulip, through being fractured, reveals the reinforcement of stereotypes in the everyday imagery we consume. Boldly present and at the same time, partially obscured, the duality in this sliced persona implies a disconnection between its physical appearance and its inner psyche.

Thomas J Price, All Sounds Turn to Noise, 2023, (bronze)

For this sculpture, Price created digitally-compiled hybrids of the facial characteristics and physical mannerisms of a broad range of people. In this way, his approach highlights the fluidity of identities beyond social and racial profiling, whilst giving visibility to bodies that are often marginalised or excluded from art history and classical sculpture.

Double consciousness:

The scholar and civil rights activist, W.E.B. Du Bois first used the term 'double consciousness' in 1897 to describe the experience of living as a black person physically within, and psychologically outside, white society. He wrote, 'it is a peculiar sensation, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity'. For Du bois, this experience of seeing the world twice over was the defining criterion of blackness.

The artists in this section both interrogate the white gaze and look beyond it. The composite portraits of Nathaniel Mary Quinn depict his subjects from both the inside, as vulnerable and sensitive, and the outside, as caricatures of black masculinity. By picturing subjects with non-naturalistic skin tones, Amy Sherald and Kerry James Marshall suggest blackness as a conceptual proposition rather than an observable condition. Noah David and Michael Armitage, on the other hand, conjure real-life events as disorientating, dreamlike scenes in which the borders between the physical and the psychological, the external and the internal, have become porous and uncertain.

Sherald's life-sized portraits of subjects with clearly African-American features but with skin tones painted in shades of grey, shift the focus away from using the sitters' skin colour to signify blackness. This enables them to claim the visibility that has long been denied to black people in art.

Sherald was commissioned ot paint the official portrait of Michelle Obama when First Lady. She used her greyscale and colour technique.

The gestural, pastel-on-paper works by Johnson depict black bodies - mostly women - on an imposing scale. Powerful, confident and at times, confrontational, Johnson's figures resist their confinement within the edges of the paper to take up the space they know they deserve. To see more of Johnson's work go here

Standing Figure with African Masks shows the artist standing side-on, directly returning the viewer's gaze. Johnson considers this work to be a response to Picasso's Les Demoselles d'Avignon.

These fragmented portraits operate within a world of visual metaphor, in which identifiable forms and features are mobilised to reveal aspects of character.

The dislocated features of the faces appear to be in continual flux, unmoored from their natural positions or shown from incongruous angles. The subjects have been turned inside out and are split between the works' two halves, exposing their humanity and vulnerability through the artist's signature assembling technique that gives form to what he dubs the 'cacophony of experience'.

Standing Figure with African Masks shows the artist standing side-on, directly returning the viewer's gaze. Johnson considers this work to be a response to Picasso's Les Demoselles d'Avignon.

Lying on his side, the young man confronts and subverts the female, reclining nude figure in Western art. Johnson suggests that, despite being presented as a confident figure of black masculinity, the boy's story has mostly been erased from history.

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Homeboy Down the Block, 2018, (oil, paint stick, oil pastel and gouache on linen)

The dislocated features of the faces appear to be in continual flux, unmoored from their natural positions or shown from incongruous angles. The subjects have been turned inside out and are split between the works' two halves, exposing their humanity and vulnerability through the artist's signature assembling technique that gives form to what he dubs the 'cacophony of experience'.

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Duckworth, 2018, (pastel and gouache on linen)

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Father Stretch my Hands, 2021, (pastel and gouache on linen)

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Buck Nasty: Player Hater's Ball, 2017, (black charcoal, pastel and gouache, gold powder on paper)

Jennifer Packer, Ivan, 2021, (oil on canvas)

Jennifer Packer, Untitled (K. Drew), 2019, (oil on canvas)

Black Wall Street represents a nightmarish scene that is an emotional memorial of the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, one of the worst incidents of racial violence in US history, in which prosperous black communities were attacked and destroyed by a racist mob.

Noah Davis, Mary Jane, 2008, (oil and acrylic on canvas)

In Mary Jane the smooth paint application on the girl's clothing contrasts starkly with the thickly applied and swirling green paint that almost envelops her, as if pulling her into the foliage behind, demonstrating Davis' ability to transport the viewer between the real and the surreal.

Armitage's paintings provide a unique staging ground for seemingly oppositional forces - figuration and abstraction, reality and surreality, lived experience and reportage, positive and negative - to find a harmonious union.

A sense of encroaching danger is a common element in Armitage's paintings. The portrait of the middle-weight boxing champion Conjestina Achieng recalls Tahitian painting by Gauguin with Achieing being tortured by nightmarish visions, much as she was criticised in the Kenyan media.

Kerry James Marshall, Nude (Spotlight, 2009, (acrylic on PVC panel)

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Painter), 2009, (acrylic on PVC)

The persistence of history:

The artists in this section are addressing the absence of black representation in Western art history. Although the black figure had long been present in painting and sculpture, up until the 20th century it had usually been white artists who depicted black people - often without names or personal stories. By contrast, the artists here are seeking to establish a record of individuals, places and memories that situate black people at the centre of historical narratives.

Barbara Walker's series Vanishing Point originates in classical Western paintings. By focusing on the black subjects in those paintings, who are often depicted in the roles of attendants, servants or enslaved people, she invites reflection on that legacy of marginalisation and erasure.

Barbara Walker, Vanishing Point 9 (David), 2018, (graphite on embossed paper)

Drawing on public archives and art collections, Walker seeks out instances of black absence in Western art history to raise questions around representation and belonging. Walker's works can be understood as vital documents of social commentary that highlight cultural and political issues in contemporary British life. From small, embossed works on paper through to large-scale oil paintings and monumental site-specific wall drawings in charcoal, Walker's wide-ranging practice initiates conversations about race, gender and power.

Drawing on public archives and art collections, Walker seeks out instances of black absence in Western art history to raise questions around representation and belonging. Walker's works can be understood as vital documents of social commentary that highlight cultural and political issues in contemporary British life. From small, embossed works on paper through to large-scale oil paintings and monumental site-specific wall drawings in charcoal, Walker's wide-ranging practice initiates conversations about race, gender and power.

Combining two paintings - one to conceal and one to reveal - is something that Kaphar has returned to frequently. In his Seeing Through Time series, he replaces the white female protagonists from neoclassical-style paintings with a black woman. This then enables the young black pageboy serving the white woman in the original work, to witness instead prominence and visibility being given to a black woman. By allowing the historic to collide with the contemporary, Kaphar creates a conversation about the representation of black people in Western art history.

Titus Kaphar, Seeing Through Time, 2018, (oil on canvas)

Kimathi Donkor, Harriet Tubman en route to Canada, 2012, (oil on canvas)

Kimathi Donkor, Nanny of the Maroons' Fifth Act of Mercy, 2012, (oil on canvas)

Kimathi Donkor, Harriet Tubman en route to Canada, 2012, (oil on canvas)

Donkor's paintings restage socially, politically and culturally important events from history to tell the often forgotten or overlooked narratives of the people who fought for freedom. Here he re-imagines historical female commanders from Africa and its diasporas. One depicts Queen Nanny, leader of the Maroon guerillas who fought the British in Jamaica during the 1700s and the other Harriet Tubman, the prominent American abolitionist who, having escaped slavery, worked to free 70 others in the 1850s. Both reference works created by painters contemporary to each subject. The portrait of Queen Nanny is based on Joshua Reynolds' Portrait of Jane Fleming (1778) a sitter whose family were involved with enslaving people in Jamaica. The portrait of Hariet Tubman explicitly references Henry Alexander Bowler's The Doubt: Can these Dry Bones Live? (1855)

Lubaina Himid, The Captain and the Mate, 2017, (acrylic on canvas)

Himid uncovers the hidden histories of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade to return to its victims the identities that were so brutally stolen from them. The artworks in this exhibition are from Himid's Le Rodeur series that reimagines an horrific incident when enslaved people being transported on a French ship, Le Rodeur, were affected by an illness that resulted in them and the ship's crew becoming permanently or temporarily, blind. The captain ordered 36 Africans, who could not work as their sight loss seemed irreversible, to be thrown overboard. As 'items lost at sea', the insured human cargo was worth more to the captain dead than alive.

Our Aliveness:

This section brings together artworks that invoke the wonder and fragility of the black everyday. In the context of a society where black presence can be subject to antipathy, the act of coming together in kinship takes on a powerful resonance. It becomes a form of liberation and an assertion of aliveness.

Forrester sees reggae and dub clubs as metaphors for city life: the mass of people moving together, yet independent of each other. In this painting, numerous, tightly packed figures appear to be moving as one, their bodies squeezed together. Reduced to outlines rendered in a palette of blue and purple, they worship the giant speakers that have replaced the DJ.

looking closer

No comments:

Post a Comment