Landscape and Imagination: from Gardens to Land Art, at Compton Verney, Warwickshire.

The exhibition showcases how landscape has changed over time: from the formal grounds of the 17th and 18th centuries, to smaller flower-filled gardens of the 19th and 20th centuries. It explores how artists have responded to those changes and how environmentally conscious land artists undertake earth moving schemes today. In this post I have concentrated on the most recent artworks.

Rather than concentrating on recognisable topographical detail, this painting is about light and colour, reflections and atmosphere.

In Japan there was a long tradition of producing paintings and prints of flowers and birds, usually associated with poetry. From the 1850s these works also became popular in Western Europe.

The Kameido shrine is famous for its wisteria, a plant that only came to Britain in 1806 (from China) and 1830 (from Japan). People visited the Kameido shrine when the wisteria came into bloom, to celebrate the coming of summer.

Henry Moore, Working Model for Two Piece Reclining Figure: Cut, 1978-9, (bronze)

Moore began experimenting with reclining figures broken into two or three parts as early as 1934. By 1959, he was creating them on a monumental scale. By separating the parts of his figures in this way, Moore felt thatt he was breaking down the boundaries of the human form, and uniting body and landscape in an indivisible whole.

The gap between the pieces provides a view of the landscape beyond and once the outline is interrupted, as Moore said, it was easier to see breasts and knees as being landscape forms, like mountains and rocks. Hence, the clever positioning of this sculpture in the gallery.

a different view

Henry Moore, Working Model for Reclining Figure: Festival, 1950, (bronze)

Henry Moore saw this as the first of his sculptures in which the space and the form are inseparable from each other. The way he opened up sculptural form to include space could be seen as parallel to the way that Capability Brown opened up space in the landscape by creating long uninterrupted views.

The artist's garden:

The works below show an intensely personal response to the beauty of gardens made by the artists themselves or by a close relative. The most notable one is the very individual garden made by Derek Jarman at Prospect Cottage, near Dungeness, which is a work of art in itself. The garden became a place of refuge and therapy for him in his final years.

Constable pays careful attention to the life of the village beyond: the thresher in the barn in the centre, the reaper in the ripe cornfield on the right. It is raining in the distance, and the shadow over the garden is a reminder of his mother's recent death, as a result of a fever brought on by gardening on a cold day.

John Nash, Wild Garden, Winter, 1959, (watercolour on paper)

In this painting, the weather is bleak and some of the trees are bent over by strong winds, but the soft blues, greens and purplish browns, along with Nash's eye for pattern, reveal hidden beauty in the austere landscape.

Paul Nash, The Garden, 1914, (pen and ink and watercolour squared in pencil on paper)

Howard Sooley, Prospect Cottage, 2012, (photographs)

Derek Jarman's garden is surreal and otherworldly, like his films. It is in an unpromising location, the shingle spit of land next to the nuclear power station at Dungeness. Around a fisherman's cottage he planted hardy species, such as sea kale, that could cope with the exposed situation and the salty air. He began with a formal layout, but as the garden grew it came to look more natural. Driftwood encloses and protects the delicate plants. With no apparent boundaries, the power station becomes part of the drama of its setting. Jarman's friend Howard Sooley was commissioned to take photographs of the garden and made many visits there.

Land Art and Environmental Art:

Land Art, also known as Earth Art or Environmental Art, emerged as a movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Its artists took art out of the gallery and the museum, often to remote locations, to work with the basic materials of the earth, soil, rock, water and vegetation.

The first Land Artists reacted against the commercialisation of art, deliberately constructing works that could not be bought or sold. They were closely linked to the emereging environmentalist movement. Often seen as a 20th century American phenomenon, pioneered by artists like Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson, this movement echoed the manipulation of land, water and vegetation in the landscape gardening of the 19th century.

More recently, artists have laid more stress on the envionment, and prefer to work with nature, rather than against it. Patricia Johanson's Fair Park Lagoon, with its practical solutions for encouraging wildlife, was a key work in this change of direction. David Nash's Ash Dome focuses on the planting and training of trees whilst Alexandra Daisy Ginsbert considers how a floweer garden looks from the perspective of bees and other pollinators.

The passage of time is an abiding theme in Land Art. Some works were designed to last for centuries, others are ephemeral. The artists are conscious of the resonances between their works and those of earliest human landscape designers, the builders of Neolithic earthworks. Charles Jencks explores this wider view of time and space, looking beyond our familiar, earthbound nature to the immensity of the stars and the solar system.

Responding to the many threats to the survival of pollinators - and hence to human survival as well - Ginsberg has created a unique artwork that invites us to see the world from a pollinator's perspective. With the Pollinator Pathmaker tool, you can experience the world as if you were a bee or butterfly, and design gardens that are friendly to pollinators. Beginners to experienced gardeners can join in this art-led campaign to create the world's largest climate-positive artwork together.

Alexandra Dairy Ginsberg, Pollinator Pathmaker: a4WNehdyCgdiKwVhXKGDBM (Human Vision, Late Spring), 2023, (tapestry thread)

Over the last twenty years, it is estimated that the numbers of flying insects in the UK have declined by as much as 60%. To raise awareness of this crisis, Ginsberg worked with horticulturalists, pollinator experts and an A1 online algorithm tool which uses empathy to design gardens that pollinators will love.

These tapestries, present an unrealised Pollinator Pathmaker edition which has been designed using the algorithm. But instead of a planted garden, we experience the digital design through the sustainable media of woven fabric. In this tapestry we see the garden as it appears to humans in late spring. In its companion piece (above) we see a garden as it would be seen by bees, butterflies and other pollinators in Ginsberg's 'pollinator vision' during early summer.

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, Rozel Point, Great Salt Lake, Utah, USA, 1970

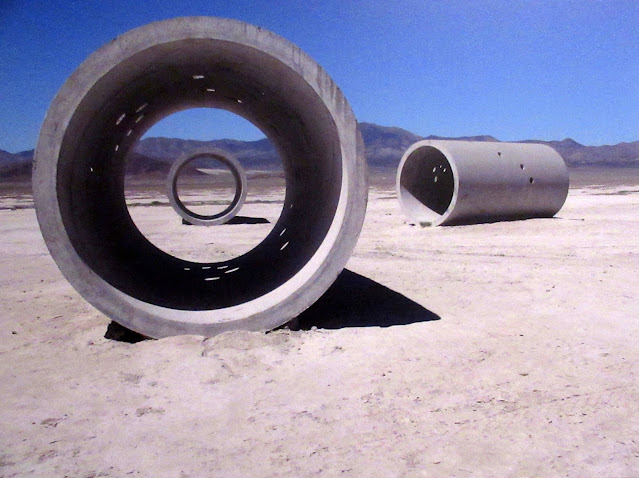

The concrete tunnels of Sun Tunnels are aligned to frame the sun as it rises and sets during the autumn and winter solstices: holes in the concrete cast projections of constellations of stars inside their surface. The installation echoes abandoned industrial landscapes.

Holt's and Smithson's two works date from the earliest years of the Land Art movement. They echo prehistoric interventions in the landscape that linked the earth to the sun and the stars. Both works encourage meditation on the passing of time.

Patricia Johanson, Fair Park Lagoon, Dallas, Texas, 1981

In 1981, the land artist Patricia Johanson was commissioned by Dallas Museum of Art to landscape a lagoon behind the museum, which was at that time a dangerous, muddy pool which was biologically dead. Her plan included large sculptures based on the forms of two native Texas plants. Bulrushes and wild rice were planted to create habitats for birds, fish and turtles. The sculptures provided walkways and bridges, enabling people to wander, play and observe wildlife.

Johanson began by making ceramic models, which she filled with water so that she could study changing colour effests and reflections in the lagoon. Fair Park Lagoon is now regarded as a milestone in the development of Land Art.

Since that time Johanson has made her name designing multi-functional urban landscapes, combining flood control, wildlife and recreational use. Like 18th century landscape gardens, her designs make use of curving paths based on natural forms rather straight lines, but unlike them her work was designed to be accessible to all.

* * *

We then watched the David Nash video which was one of the highpoints of the exhibition:

David Nash, Ash Dome, 1977 - onwards (film made with Culture Colony)

In 1977 David Nash planted a circle of 22 ash trees and trained them to grow into a dome, at a secret location in Wales. Since that time, he has tended the trees, mulching them and pruning them regularly. He has made many drawings of them over the years, often using charcoal, a material that is itself made from trees. Nash hoped the trees would outlive him, but sadly they are now afflicted by ash dieback, a disease caused by a fungus which is projected to kill up to 80% of ash trees across the UK.

Nash has updated the film with new footage relating to ash dieback

We are told: Ash dieback disease arrives in the UK in 2012. It is believed that the fungus originated in Asia and first appeared in Eastern Europe in 1992. It gradually spread westwards, decimating the ash trees of Northern Europe. Ash dieback is caused by a fungus that spreads its spores on the wind. It's evolved to affect the water circulation system of the tree, just under the bark. Lack of water causes the branches to die from the growing tips back into the major limbs and trunk.

Finally: Having researched possible prevention, it was decided to follow the original concept. Growing a sculpture, working with the natural energies of the site, and accept the fungus as a natural energy. A ring of 22 oak saplings were planted around the ailing Ash Dome to continue the idea of growing a space.

No comments:

Post a Comment