Hannah Hoch at the Whitechapel Gallery.

An artistic and cultural pioneer, a member of Berlin's Dada movement in the 1920s and a driving force in the development of 20th century collage, Hoch lived during a time of tremendous social change and she created a humorous and moving commentary on the chaos of the modern world and the turmoil of the political change that accompanied the carnage of WWI. She believed in artistic freedom and she questioned conventional ideas about relationships, beauty and the making of art. She believed that the purpose of art was to change society and that the artist had to take a stance. Her collages explore the concept of the 'New Woman' questioning traditional gender and racial stereotypes.

In line with the Dadaist belief of taking up 'scissors and cutting out all [they] required from paintings and photographic representations', Hoch spliced together images taken from fashion magazines, newspapers and illustrated journals. She described what she did as 'remounting, cutting up, sticking down and activating'. Grimacing heads, grotesque figures out of the fused features of children, adults, animals and artefacts: her compositions play with gender stereotypes. Responding to a fragmented world where diversity and difference were frowned upon or persecuted rather than being celebrated, she made fragmented art. She embraced diversity and difference, questioned accepted ideas of beauty and constructions of gender, and showed the alienation of our fragmented society. 'I would like to blur the firm borders that we human beings, cocksure as we are, are inclined to erect around everything that is accessible to us'. By deconstructing accepted images she re-assembled them into new ones, giving them new meaning.

She managed to escape persecution by the Nazis. During WWII, she kept a low profile in a small house in the suburbs of Berlin - she described those years as 'twelve years of misery - forced on us by a mad, inhuman, bestial clique'.

Too much reflection on the glass of the pictures meant that the quality of some of the photographs I took is very poor - apologies for that.

Nude, (pencil drawing)

Two Nudes (Couple), 1912 (gouache)

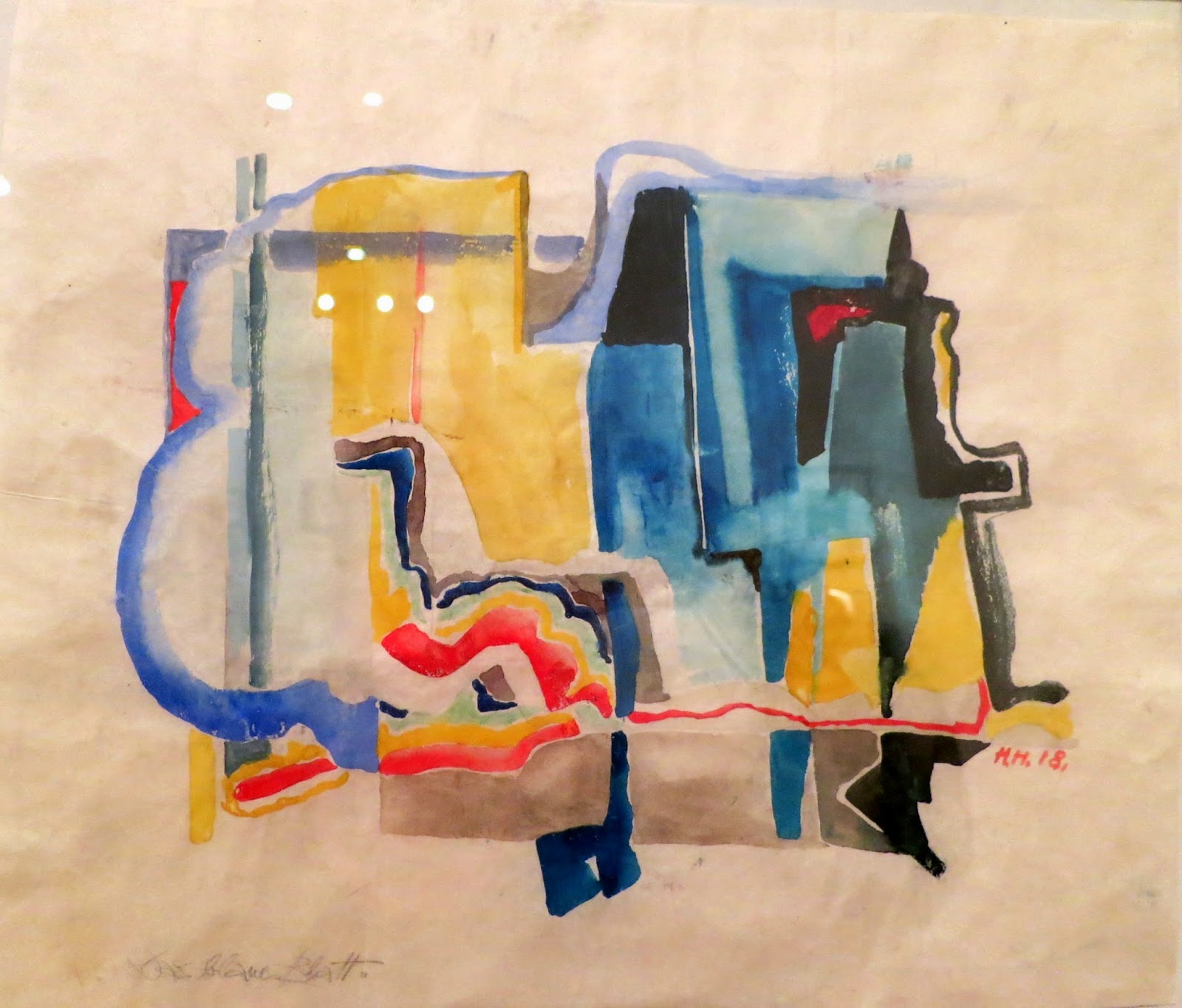

The Blue Page, 1918 (watercolour on tracing paper)

On Gold Paper, 1920 (collage)

Heads of State, 1920

A photograph of German president Friedrich Ebert and Gustav Noske, the defence minister, pictured in their bathing suits, their paunchy figures atop an embroidery pattern of a woman with a parasol, surrounded by flowers and butterflies.

High Finance, 1923 (collage)

Two towering male figures striding across an urban landscape. In front of a backdrop of industrial and military imagery the figures dwarf the diminutive buildings and the inhabitants they tread upon.

The work bears a dedication to the Bauhaus teacher: 'for Moholy-Nagy from Hannah Hoch'.

The Tragedienne, 1924, (collage)

The Melancholic, 1925, (collage)

Equilibre, 1925, (gouache with watercolour)

Love, 1926 (collage)

A mocking look at relationships between men and women. Using the image of a doll which is meant to represent innocence, Hoch's doll has a sinister look due to the fact that the picture has been cut at odd angles. Neither the man nor the doll look at each other.

Two-Faced, 1928, (collage)

From An Ethnographic Museum, 1930 (collage)

The Strong Men, 1931, (collage)

Made for a Party, 1936 (collage)

Dream Voyage, 1947, (collage)

Little Sun, 1969

* * *

Finally, her most well-known work. This was not included in the exhibition but I have added it here, courtesy of the Guardian.

Cut With the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, 1919.

In the top right corner are the forces of anti-dada: representatives of the late empire, the new Weimar government and the army. Below, in the dada corner are artists and radicals. Raoul Hausmann is being extruded by a machine to which is affixed the head of Karl Marx. In the bottom right corner is a small map showing the European countries in which women could then vote.

Photograph of the artist, 1926

Sources:

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jan/09/hannah-hoch-art-punk-whitechapel

The exhibition leaflet.

Her work is still striking now, just imagine how powerful it must have looked at the time. I am very much looking forward to reading the catalogue.

ReplyDeleteYou are absolutely right: it must have been so powerful, new and exciting at the time, and it still is. I loved the exhibition.

Delete