Anthony Gormley at the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Iron Baby, 1999

Once we got into the galleries, we entered hell. We visited on a Tuesday so as to avoid the crowds and yet, I have never seen so many people at an exhibition. Absolute mayhem. Every room was packed with people, there were screaming kids running around, climbing on the sculptures, bumping into people. Absolute hell. I hated every minute of it. We were very selective in what we looked at, and ignored the prints even though they were very fine. My overwhelming feeling was to get out. Did I regret seeing the exhibition? Absolutely not. I love Gormleys work and am glad that I saw the exhibition despite the conditions.

It's a difficult one, isn't it? It's great that so many people want to visit art galleries - Clement Greenberg called them the Cathedrals of the Twentieth Century - but at the same time, the whole experience becomes unpleasant and overwhelming.

In the first room, the Slabworks, 2019, are to be found.

14 sculptures are distributed across the floor. They are hard-edged steel slabs.

At first they appear to be building-like constructions

but they are revealed as human forms. Despite this extreme abstraction of form, the finely-tuned proportions trigger our recognition.

***

In the second gallery the experimental origins of Gormley's practice during the late 1970s and 1980s are explored. The main influences here are Art Povera (known for transforming 'poor' materials) and Land Art, which saw artists working out in the landscape and bringing nature into the gallery.

One Apple bisects the space of the gallery.

53 lead cases record the growth of an apple from the first petal to fall from the blossom, through the stages of ripening to mature fruit. Each contains the died remains of the fresh apple which was moulded to make the form for each case.

The apple recalls the forbidden fruit of the Garden of Eden and Newton's apple that inspired his law of gravity. In common with other sculptures gathered here, One Apple reveals Gormley's preoccupation with ideas of expansion in time and space.

Blanket Drawing V, 1983, (clay and blanket)

Land Sea and Air, 1977-79, (lead, stone, water and air)

Three apparently hidden forms that pose the question: what is inside? Hidden from view we are left to imagine their interiors: a rock, water and empty space. Collectively, they represent the necessary conditions for life: in the artist's words, 'they are seeds for the future'. Gormley went on to apply the technique of wrapping and beating sheets of lead to casts of his own body to create his famous 'body cases'.

Mother's Pride V, 2019, (bread and wax)

looking closer

Full Bowl, 1977-78, (lead)

Clearing VII, 2019:

This 'drawing in space', as the artist calls it, is made from approximately 8 kilometres of square section aluminium tube, coiled and allowed to expand until restricted by the floor, walls and ceiling. The wild orbits of the line evoke the sub-atomic paths of electrons, or the frantic scribbles of a child.

Clearing VII challenges the boundaries of sculpture: the space occupied by the piece and the viewer are one. No longer a single object, the work become a spatial 'field'. Choosing a route involved a physical negotiation: stepping over, crouching or turning sideways, we became part of this dynamic artwork.

The expression on this woman's face encapsulated the atmosphere that pervaded this exhibition when we visited: frantic, manic.

Subject II, 2019

A single life-size body form, with head bent, contemplates the ground on which it stands.

This sculpture tests the boundary between the body and space; the 'skin' dissolves and the imagined surface shifts as we move around the dense lattice structure.

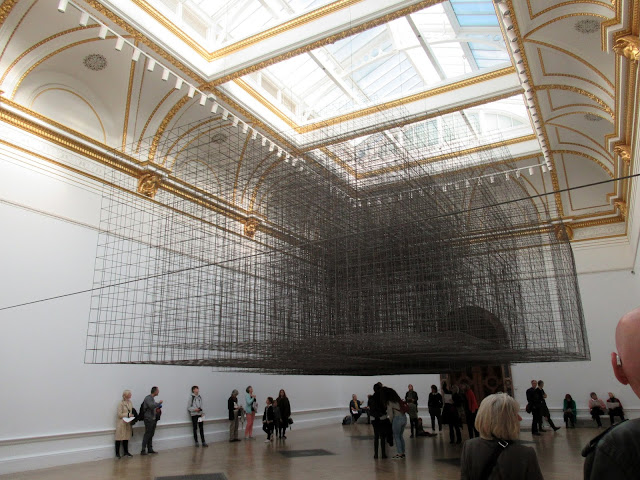

Matrix III, 2019, (approx 6 tonnes of 6 mm steel reinforcing mesh)

Lost Horizon, 2008, (24 cast iron bodyforms)

During the 1980s Gormley began to work with cast iron, which offered durability for works outdoors. The process starts in the same way as the lead 'body cases': the artist remains still while he is encased in wet plaster. The iron casts in this installation are generated serially from six moulds of similar poses, each one registering 'a lived moment of time'. For Gormley, when we close our eyes, but are conscious and aware, we occupy 'another kind of space, without co-ordinates'.

Lost Horizon I, as the title implies, denies us the distant horizontal line that we use to orientate ourselves. Many of Gormley's outdoor works consist of 'fields' of figures, placed across large areas in deserts, up mountains and on beaches. In Another Place for example, the bodies draw our attention to the horizon, and establish a link between the expanse of the landscape, and our capacity to 'go places' in our minds.

Here, inside the gallery, gravity appears to be defied and space folds in on itself: bodies project from all sides, at odds with one another. Although the works are perpendicular to the spectacular architecture of the room, the effect as we move between them is disorienting. Of course, the level horizon bellies the roundness of the earth. As we live on a ball and not a flat plane, the works around us could be understood to represent the natural orientation of humans around the globe.

Body and Fruit, 1991-93

Body, 1991-93 and Fruit, 1991-93, (cast iron and air)

These two sculptures originate from the artist's body held tightly in a foetal position.

Concrete Works, 1990-93:

At first glance, these works appear as nothing more than concrete blocks. In fact, each conceals a void in the form of a body. The feet, hands and head pass through the edges, allowing glimpses into the passages formed by the neck, arms, legs and torso. The interior surfaces of the voids retain the inverse impression of the skin. In revealing the familiar body as a strange absence, the works point to mortality.

Cave, 2019, (approx. 27 tonnes of weathering steel)

A sculpture on an architectural scale. At the doorway we had the choice of either entering a constricted passageway, or to navigate around the outside.

We joined the queue to enter the passageway

We were given advice on how to enter as we were warned it would be very dark and very constricted

half-way through we came to a clearing

and then darkness enveloped us again.

For Gormley, it is when we close eyes that we most readily experience our body as a place: 'that experience of interiorised darkness is not so different to the darkness of the night sky; the darkness of the body and deep space are a continuum'. Inside Cave, the angular, winding cavern slows our passage through, and we must literally feel our way, relying on our senses to guide us through the darkness as soft shafts of light reflect off facets of the sculpture.

We were then able to walk around the structure.

From above, the jostling cuboid structures are revealed as a vast, hollow human form, crouched on its side.

Here the body is transformed into a collapsed architecture that deliberately contrasts with the regular geometry and refined decoration of the gallery space.

Host, 2019

We stood by the door looking at an expanse of clay and seawater.

Is this an image of destruction - a devastating flood? Or of potential creation? Host embodies the raw conditions in which life might emerge, a kind of primordial soup of matter, space and time.

Pile I, 2007 (clay) and Pile II, 2018, (clay)

No comments:

Post a Comment