'The nature of trees and grass is one thing, but there are many degrees of nature. Concrete can be nature. Interstellar spaces are also nature. There is human nature. In the city, you have to have a new nature. Maybe you have to create that nature'. Isamu Nogushi, 1970.

A new nature by Isamu Nogushi, at the White Cube gallery, Bermondsey.

The exhibition takes its title from a talk Nogushi gave to students at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1970 where he urged them to forge 'a new nature' from the materials of urbanisation and technology they encountered around them. Bringing together several bodies of work that reflect the artist's attempts to make us conscious of his broader understanding of nature, the works on show employ industrial methods and materials, yet appeal to our awareness of what is organic.

The main gallery space:

The entrance corridor is dominated by the Octetra, a modular geometric system Noguchi developed in the 1960s. Formulated by his friend R. Buckminster Fuller's theories about the fundamental structures of natural forms - each element is a truncated tetrahedron - they can be endlessly reconfigured. Though the earliest examples, for a playground in Japan (1965-66) and the plaza in front of Spoleto Cathedral in Italy (1968) were made in concrete, the five configurations here are made of fibreglass, a material Noguchi wanted to use but was not yet available to him.

'Industrial process has its own secret nature - its own entropy, its own cycle of birth and dissolution... We try hard to subject the industrial process to man's [sic] supervision'. Isamu Nogushi, 1982.

Octetra (one element), 1968, (fibreglass reinforced plastic and paint)

Octetra (two element), 1968, (fibreglass reinforced plastic and paint)

Octetra (three element), 1968, (fibreglass reinforced plastic and paint)

Neo-lithic, 1982-83, (hot dipped galvanized steel)

Sky-mirror, 1982-83, (hot-dipped galvanized steel)

Akari Lanterns:

A whole separate gallery space taken up by the Akari lanterns. 'Inherent in Akari are lightness and fragility. They seem to offer a magical unfolding away from the material world', says Nogushi.

Nogushi's Akari lanterns, or light sculptures, epitomise his efforts to expand the concept, potential and purpose of sculpture. Useful, affordable, easily stored and shipped, their qualities are antithetical to our preconceived notions of sculpture. They encapsulate his interest in iterating upon old traditions, his consideration of heritage and the ways in which these crafts can be pushed into the future as well as an openness to new technologies.

Weightless and uplifting, their metaphorical and actual lightness and natural life-giving warmth offer, as he said: '

a foil to our harsh, mechanized existence'.

Ceiling and Waterfall, 666 Fifth Avenue, (1956-57):

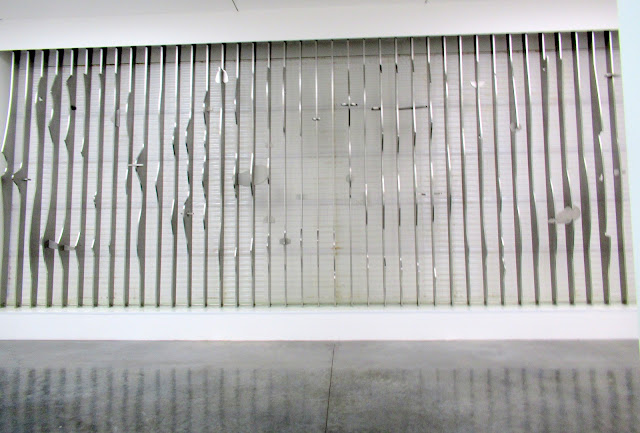

In 1955, the architect Robert Carson approached Noguchi about repurposing an unrealised design for a bank lobby in Texas for a new office building across the street from the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. Noguchi agreed to re-conceive what was initially a wall relief as a ceiling sculpture, on the condition that he could also make a waterfall.

Noguchi transformed what was a severe, modernist space of black and white marble into his favourite thing: an imaginary landscape and buffer from urban noise - a sea of clouds and the sound of falling water.

It was the sound of falling water that alerted us and made us enter this separate gallery off the main corridor.

An undulating, wave-like arrangement of aluminium and stainless steel, with water cascading down it

onto the floor.

Later, we saw someone mopping the floor

In the corner, a small sculpture

Magritte's Stone, 1982-83, (hot-dipped galvanized steel)

Behind

Waterfall in a vast space, is

Ceiling: a similar undulating, wave-like arrangement of aluminium and stainless steel

from the back of this space one can see the wall where

Waterfall cascades down onto the floor

It's a dream-like space, the light that reflects from the ceiling creating cloud-like formations on the floor

In the middle of it all, sits

Sparrow, 1982-83, (hot-dipped galvanized steel)

Derived from Heaven:

The installation in this gallery space takes its inspiration from Noguchi's ideas for simple terracing for playgrounds as well as

Heaven (1977-78), a complex step-pyramid environment he designed for the atrium of Segetsu Kaikan, Tokyo.

Heaven functioned as a public plaza for events and exhibitions, and embodied Noguchi's belief in empiricism as a form of intelligence. This is a homage to the artist's desire to extend sculpture to lotal environments.

Galvanized steel sculptures:

Late in life, through experimening with the Japanese crafts of kirigami and origami and industrial sheet metal manufacture, Noguchi produced a series of twenty-six galvanized steel sculptures. The sculptures represent a virtual retrospective of the artist's wide-ranging visual vocabulary - landscapes, bodies, abstract spatial concepts and natural forces - and offer a bridge between the natural and the humanmade. Process-driven, playful, and oriented towards an increasingly urban environment, they are archetypal late works of this great artist.

No comments:

Post a Comment