Ali Kazim, at the Ashmolean, Oxford.

Ali Kazim was born in 1979 in Pakistan, where he lives and works as a multidisciplinary artist. In 2019, Kazim was invited to the Ashmolean. He spent days browsing through the museum's collection, examining objects up close, many of which became references in his work.

Kazim believes objects can connect us, directly and viscerally, to the people who originally made and used them. His engagement with the material and visual traditions encourages the viewer in turn to reflect on how the past informs and influences the present. His works are charged with introspection and engage with space between the self and the divine. Space can act as a bridge to an experience beyond history.

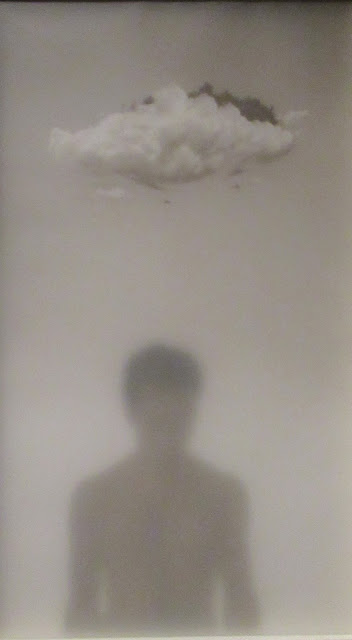

Untitled (self-portrait with cloud), 2014, (watercolour pigments on paper and dry pigments on mylar)

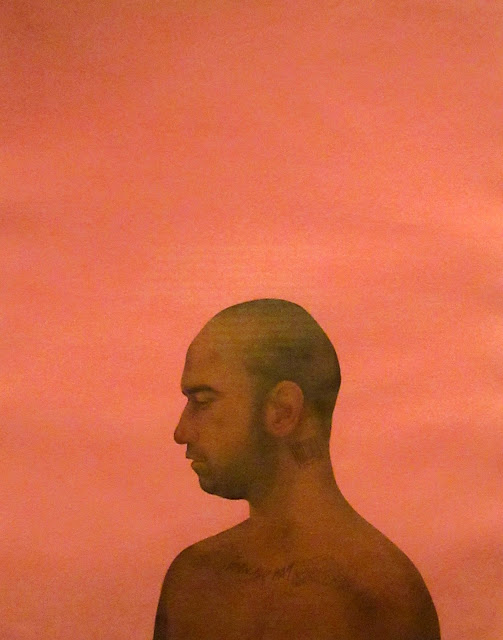

Untitled (self-portrait diptych), 2012, (watercolour pigment on paper and dry pigments on mylar)

Kazim's painting makes a clear reference to its Gandharan inspiration: a fragmentary figure from the Ashmolean's collection which is posted below. This grey schist figure of a male mourner, kneeling and bent over in visceral agony, is transformed by Kazim into an exercise in re-enactment, the one visible eye strangely turned halfway towards the viewer. Looking closely at the Gandharan sculpture of the Mourner, Kazim sees a young man in pain, with grief etched on his face, body and posture almost as if he was self-punishing.

Mourner, Gandharan sculpture

Close examination of the paintings show the details of the delicate brush strokes in powder pigments, and the use of the wash technique to make boundaries less distinct. The soft wash evokes an emotive quality, adding to the suggestion of a contemplative, solitary mood. He compares the process of the washing of layers of paint to human ablutions: the ritual washing of the hands, feet and face required before prayer in Islam.

There is a grace about Kazim's subjects, who do not sit for the portraits. The individuals are often, though not always, strangers, photographed on the street, because they attract the artist's interest, or references found in earlier works of art. For the artist, it is the medium and the colours that set the mood of the work, rather than the personality of the subject. Even as the impact of globalisation enables people to move an construct complex identities, Kazim remains fascinated with those elements of identity that individuals continue to hold close, and which help them make sense of who they are and where they come from.

Kazim presented an installation entitled Conference of Birds at the Lahore Biennale (2020). This revealed 3000 sundried, unfired clay birds which, displayed outside within a ruined building literally dissolved in the rain.

The installation commemorated all the unsung, unnamed heroes of a large collective. Not everyone makes it in life, but everyone deserves to be remembered.

Kazim's references include the Indus Delta, where migratory birds come to rest and people hunt them. Human impact on biodiversity reflects the experience of those birds that do not survive the journey. Birds no longer speak for mankind, but humans control their survival or extinction.

Gandhara Connections and Votive Stupas:

Ancient Gandhara, located in what is today northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, was for centuries a thriving centre of trade along the Silk Road. Buddhism, which had emerged from India, was embraced in Gandhara, where Buddhist stupas and monasteries were constructed.

Resonating with Buddhist reliquaries and votive stupas, Kazim transforms works into three-dimensional miniature forms. These beautiful and tactile miniature terracotta sculptures minic the ancient shapes in clay, but do not demand interpretation.

The stupa was a reliquary shrine, often small but sometimes colossal in scale. It took the form of a mound or 'dome', a place to hold physical relics directly or indirectly associated with the Buddha. Miniature stupas were commissioned by Buddhists and offered to monasteries. Considered auspicious to be buried in a place visited by the Buddha, or where his relics were kept, sometimes human ashes and bones have been found in such votive offerings.

Untitled (Mara's Army), 2020, (watercolour pigment on paper)

No comments:

Post a Comment