The Russian Avant-Garde, at the Museum of Modern Art, Stockholm.

Although the Russian avant-garde is not a homogeneous group of artists, they were all intent on expressing the revolutionary political changes and social developments that were taking place during the first three decades of the 20th century in Russia and the Soviet Union. They were inspired both by the latest trends in contemporary art of the West, such as Cubism and Italian Futurism, and by the folk art and icon painting of the East. Many of the artists, including Tatlin, Popova, Ekster and Rodchenko, travelled to Paris, one of the key centres for the start of abstract art, where they studied and lived. The Futurists championed modern life; they worshipped the city and progress, speeding automobiles, electric light and constant movement. The world of the 'beautiful' machines also set its stamp on the work of Fernand Leger, who was a key source of inspiration for many of the Russian artists.

Following the October Revolution in 1917 the new radical art of the Soviet state was first supported and then suppressed in the ideological and political struggles of the period. The turning-point came the years before Lenin's death in 1924, and from 1934 Socialist Realism was the only art form endorsed by the state. The Russian Constructivists moved away from painting pictures after the October Revolution; they were opposed to the idea of art as something independent and autonomous. Modern Soviet society was to be fashioned using abstract forms and functional environments. In contrast with the situation in the art metropolises of Paris and Berlin, a large number of women artists formed part of the Russian avant-garde and they were on an equal footing with their male colleagues.

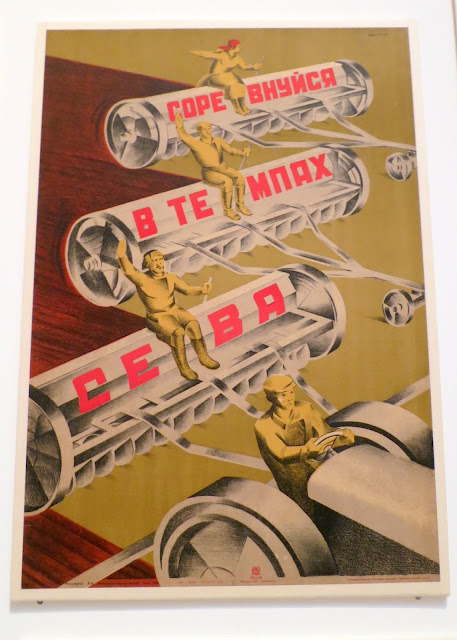

Until the death of Lenin and Stalin's takeover, the new Soviet state was the only country in which abstract art enjoyed official recognition. These artists were fascinated by the new media and experimented with the possibilities offered by photography and motion-picture film, which were closely associated with the modern city and the new society being constructed. The poster too, became a new form of expression and an important ideological instrument that many artists were keen to work with.

Vladimir Tatlin, Model for Monument for the 3rd International, 1919-1920/1968/1976

The architecture and utopian structure of the tower reflect the political vision of the Russian revolutionaries in the years immediately after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. The monument was supposed to be built with modern materials such as steel and glass. The geometric parts of the tower would house the administration headquarters of the International, and each part would rotate around its own axis at different speeds - the smaller the section, the faster it would spin. The monument, a synthesis of painting, sculpture and architecture, would have been taller than the Eiffel Tower. Several models were made in wood, but a full-scale version was never built.

Vladimir Tatlin, Reclining Nude, 1911-1913

Lioubov Popova, Space-Force Construction, 1921

Anna-Chaja Kagan, Syprematistische Komposition, 1922-1923

Alexandr Rodtjenko, Spatial Construction No. 9, Circle in a Circle, 1920-1921

Ivan Kljun, Composition with Yellow Sphere, 1921

Wassily Kandinsky, Green Split, 1925

Alesandr Rodtjenko, Spatial Construction No. 23, 1921

Vladimir Tatlin, Untitled, 1968

The museum has a considerable collection of Bolshevik posters and below are some of them: