at Compton Verney, Warwickshire.

The title of this exhibition is taken from what Dora Carrington wrote in a letter explaining why she chose not to marry at the time, stating that to do so would diminish 'a spirit inside'. The works exhibited have been taken from the Ingram Collection and The Women's Art Collection.

Dora Carrington, Iris Tree on a Horse, 1920, (oil, ink, silver foil and mixed media on glass)

Carrington's depiction of her friend, the actress, model and poet Iris Tree uses chivalric imagery, showing her as a knight galloping fearlessly atop a horse. Tree was famed for her bobbed hair and here appears like an early saint or medieval heroine, a symbol of female resilience and rebellion. This is one of Carrington's so-called 'tinselled pictures' which she made using silver foil. They became popular and she sold them regularly as well as gifting them to friends. Owned by Tree, the work had a talismatic quality for her. She kept it with her and displayed it stacked against books in her one-room apartment in Rome.

Eileen Agar, The Sower, (watercolour and gouache)

In this work, Agar reimagines nature as a realm of symbolic complexity and imaginative possibilities. The foreshortened perspective and abstract shapes give a sense of timelessness to the landscape. The imagery of the sower, and of sowing seeds, holds a metaphorical resonance, conveying themes of growth, renewal and the cycle of life.

Agar was a prominent British artist known for her significant contributions to Surrealism. However, with a diverse body of work encompassing painting, sculpture, collage and photography, she was unwilling to be classified simply as a Surrealist artist.

Paula Rego, Ines de Castro (pastel on paper)

Rego was often inspired by the tradition al folk tales told to her by her grandmother. Ines de Castro depicts the macabre tale of a 14th century Portuguese noblewoman of the same name, who according to folklore, was murdered by King ALfonso IV. Her love, Prince Pedro, swore revenge on his father. After taking the crown for himself, Pedro exhumed and crowned Ines as his queen. Rego places the focus on Ines, so that she dominates the composition, even in death. The gold colour palette and the characters' courtly pose makes the work seem semi-sacred and it shares qualities with medieval illuminated manuscripts. The image reflects how women have historically been used as pawns in political war games.

Kate Montgomery, Nightwatch, 1996, (casein tempera on wood)

Roberta Booth, Ride of the Valkyrie, (oil on canvas)

The Ride of the Valkyrie refers to women in Norse mythology who guide the souls of dead warriors to Valhalla, a majestic hall on Asgard, the home of the gods. Booth's surreal forms foster a sense of mystery and reflect the intangible nature of our own imaginations - what seem like winged figures flying through sky morph into abstract, mechanistic, metallic forms, seemingly familiar yet unknowable.

Anna Liber Lewis, Holy Trinity, 2016, (oil on canvas)

Lewis uses her paintings as an act of female resistance, employing abstraction to redefine representations of the female body. The Christian Holy Trinity (Father, Son and Holy Ghost) form three points on the triangle. Lewis associates this triangle with another triangle, an abstract vulva. In doing so, she imbues the female form with a sacred power, challenging the historically patriarchal structures of the church which have often made genitalia a source of shame.

In the background, peaecock feathers form a yin-yang symbol. In Greek mythology, the peacock is linked to the goddess Hera and symbolises beauty, power and immortality. Peacock feathers are often seen as a symbol of protection and watchfulness. The cyclic shedding and regrowth of peacock feathers have led to interpretations of renewal, rebirth, and resurrection in various cultures.

Leonora Carrington, Tuesday, 1987, (lithograph)

Tiny trees grow up from knee-high hills, a hyena sits on the shoulder of a small headed figure, a blue bird balanced on its paw. Tuesday conjures an alternative world where the human, natural and spiritual are brought together in a Surrealist landscape populated by mythical creatures. Carrington was drawn to mythology in search of a celebration of the feminime power that she channelled in her artistic work as well as in her writing. In this dreamlike space, traditional spatial relationships have collapsed as has our understanding of scale. We are encouraged to surrender our preconceptions of the world around us.

Nengi Omuku, Naomi, 2021, (giclee print on paper)

Winifred Nicholson, Woman Playing a Piano (Vera Moore), 1930, (oil on canvas)

Bridget Riley, Woman at a Tea-Table, 1950s (coloured crayons and pastel)

This work was made before Riley became known for her innovative use of geometric patterns and optical illusions to create artworks that produce visual effects of movement and vibration. Rooted in observation, this work is an image of a woman occupying an internal world, enjoying a moment's peace as the objects around her shimmer in glistening, heightened colour.

Dod Procter, The Golden Girl, 1930, (oil on canvas)

The elegant simplicity of Procter's paintings was part of a new classicism, a move away from the machine-age works that were prominent in the years before WWI.

Sarah Cawkwell, Focus, 2011, (charcoal on paper)

Tiffanie Delune, No More Battlefields, only Flowers, 2022, (mixed media on paper)

This work is an imaginary portrait of Delune's father with the face of the artists' son on his forehead. The child appears like a 'third eye' - a mystical invisible eye which symbolises vision beyond ordinary sight, something emphasised by the face's closed eyes.

Linder, Hiding but Still not Knowing, 1981-2010, (C-type print on original negative on photographic paper)

In this photograph parts of Linder's face are obscured to challenge traditional depictions of feminine beauty. In this self-portrait, Linder uses cliches from fashion to create the appearance of glamour. They are undermined however, by her greasy hair, badly applied lipstick and the holes in her lace top. The alluring yet sinister image questions the way in which women fashion themselves and for whom.

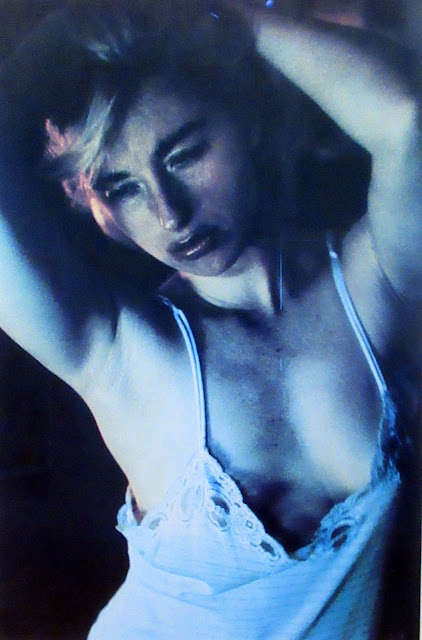

Cindy Sherman, Untitled 103, 1982, (photograph)

Sherman appears here in the clothing and suggestive pose of a glamour model. At first sight, nothing appears amiss. However, close inspection reveals smeared lipstick and a tattered nightgown. Her facial expression is one of pent-up sadness.

Throughout her career, Sherman has explored the construction of identity by transforming herself into different characters and adopting different appearances which she photographs. Through these guises, she explores the performative nature of gender and celebrity, often deconstructing feminine stereotypes. In doing so, she subverts our perception of the world around us to highlight how unreliable stereotypes can be when trying to understand a more complicated reality.

To see more of Sherman's work you can go here , here , here and here

Elisabeth Frink, Bird, 1958, (bronze with dark brown patina)

With elongated legs, wings pinned back against ibs body and an arched back, Frink's sculpture of a bird is taut with energy. Bird forms were a preoccupation for Frink in the early years of her career.

Whilst she resisted symbolic readings of her sculptures, Frink saw her bird sculptures as 'vehicles for strong feelings of pain, tension, aggression and predatoriness'. Through these works, she sought to come to terms with the aftermath of WWII, reconciling heroic rhetoric with a gruesome reality. Heavily textured, her birds combine an animalistic violence with she sleek geometry of military aircraft.

To see more of Frink's work you can go here , and here

Soheila Sokhanvari, Rhapsody of Innocence (Portrait of Monir Vakili), 2022, (egg tempera and 23.5 carat gold on calf vellum)

Sokhanvari's work deals with contemporary politics, focusing on Iran before the Revolution of 1979. This work is part of a series of portraits of women in pre-revolutionary Iran. This painting depicts the Iranian opera singer Monir Vakili who established the first opera company in Tehran. After the revolution Vakili was forced to flee Iran and tragically died in a car accident aged 59. Sokhanvari uses traditional Persian miniature techniques to create modern day illuminations, a process she learnt from her father. Through her close, intensive focus on her subjects, she seeks to bring them back to life, regniting interest in their stories and significance.

Rose Wylie, Billie Piper (A Combo Painting), 2014, (oil and watercolour on unstretched canvas and paper)

Eileen Cooper, Perpetual Spring, 2016, (oil on canvas)

Two women are entangled. Are they dancing, fighting, struggling? Twisting branches and foliage fills the remaining space - the image is dynamic, colourful and highly expressive. The two women are different but complementary - taut straight limbs versus bent, rounded ones and white versus black costume. Their arms link to form a circle showing the interconnectedness of the figures. Cooper's work often engages with psychology. Here we see perhaps the two sides of one individual. The buds emerging from the branches of the trees perhaps suggest that out of this internal struggle will come a fruitful resolution.