John Craxton, (1922-2000) enjoyed a charmed existence. Superbly talented and supremely fortunate, he was a heroic hedonist - living for pleasure and painting it too. Cosmopolitan and nomadic, he found early fame as an artist in war-time London, but always longed to live and work in Greece. He landed in Athens, aged 23 in the spring of 1946, and enduring joy coloured his ensuing pictures. Exploring the Aegean over blissful decades, his senses were completely seduced. He was perfectly alive in each exquisite moment.

From that moment of ecstatic arrival until his death, virtually every Craxton picture paid homage to the life, light and landscapes of Greece. 'I can't tell you how delicious this country is and the lovely hot sun all day, and at night tavernas: hot prawns in olive oil and a great wine and the soft sweet smell of Greek pine trees. I shall never come home. How can I'? He wrote to a friend. And to another friend: 'I'm off again in a day to an island where lemons grow and oranges melt in the mouth and goats snatch the last fig leaves off small trees, the corn is yellow and rustles and the sea is harplike on volcanic shores. Saw the Marx brothers in an open air cinema and the walls were made of honeysuckle'.

With much of his work never previously exhibited, he can only now be recognised as an unrivalled portraitist of Greek faces and places from the middle of the 20th century. He had many famous friends but preferred to depict ordinary people - shepherds and their families, sailors and soldiers; the company he loved best.

Never passing an exam in his life, not even in art - save for the test to drive his beloved motorbikes - he just went his own way. His was an anarchic spirit of self-taught erudition, a famous wit whether speaking in English or Greek. 'Not having a motorbike made me feel like a centaur turning into a rocking horse', he once explained. For all his brilliance, he was essentially an innocent abroad. Great courage - or recklessness - got him into trouble. When exiled from Greece under the dictatorship of the Colonels, it was said that his jokes had run away with him - mocking authority once too often. His affectionate and unabashed pictures reflect an empathy for everyone while also making him an important figure in the history of the gay rights movement.

His first responses to the Aegean had been influenced by Picasso and Miro. Gradually he absorbed all the layers of creative history - sculpture from antiquity, Byzantine mosaics, Cretan icons - to embrace ancient and modern within the same ambitious picture. Besides the animals he loved so dearly, his human figures are clearly modern models - companions of the artist. But they also have a deeper resonance. The octopus fisher leaps from Greek myth; the butcher recalls the Ancient Agora of Athens; the Cretan shepherd in combat with nature relates to wild bull capture depicted on Minoan inspired gold cups from a royal tomb in Sparta.

John Craxton scorned art-world reputations. He never cared to finish his paintings, let alone to sell them. Their message - and paradox - is that he much preferred life to art: Greek life most of all.

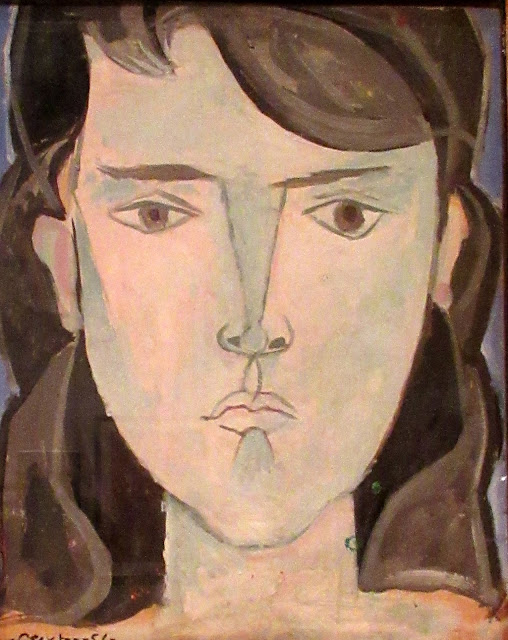

Self-Portrait, 1946-47, (oil on paper)

In 1946 he found himself in Greece for the first time. His art exploded from darkness into light and from monochrome into brilliant linear colour.

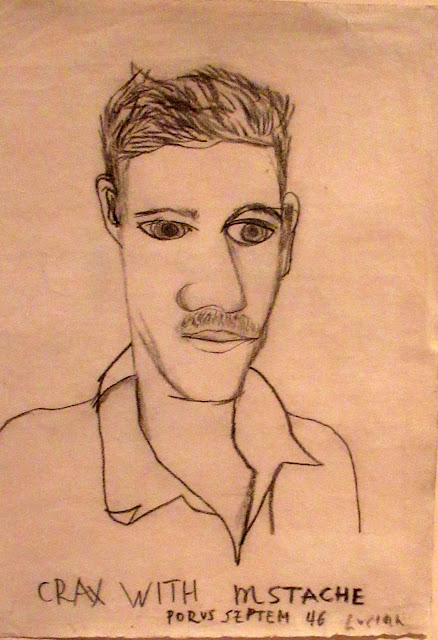

Meeting up with Joan and Patrick Leigh Fermor, he was directed to his first Greek island, Poros. This was his first base for a first decade of extensive exploration, joined at first by Lucian Freud. Here began a long friendship with the poet George Seferis.

Aged Cretan, 1948, (oil on canvas)

Rampant Goat, 1946, (pencil on paper)

Besides depicting Greek people, John Craxton was a consummate portraitist of Greek goats. He admired their resilience and mythology - from Zeus being raised by a goat to be king of gods, to Pan, god of flocks and shepherds.

Tall Goat, 1947, (oil on wood)

Chestnut Roaster, 1956, (watercolour on paper)

This painting of a girl on a Poros beach was a guide for Margot Fonteyn in Daphnis and Chloe, designed by John Craxton in London in 1951. The ballet, a Fonteyn favourite, had music by Ravel, a Longus story from Ancient Greece and choreography by Frederick Ashton. The Craxton decor comprised scenes from Poros and Crete and modern Greek dress.

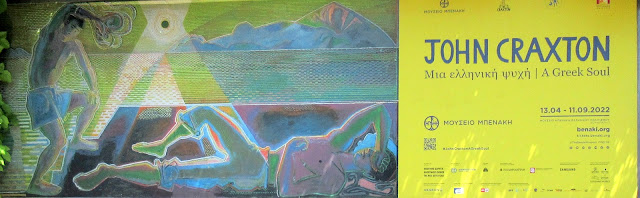

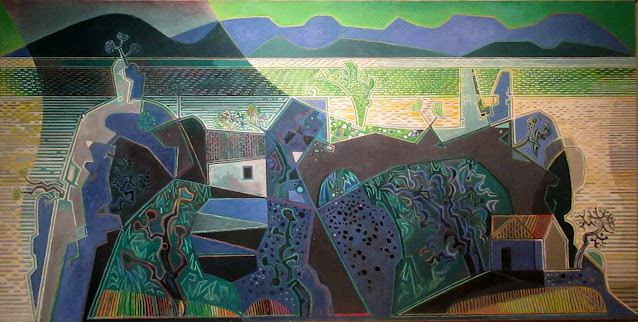

Landscape with Bathers, 1951, (oil on canvas)

After the launch of Daphnis and Chloe, John Craxton, Frederick Ashton, Margot Fonteyn and Joan and Paddy Leigh Fermor were treated to a Greek island cruise. Fonteyn used a deck rail as a ballet barre; Paddy Leigh Fermor wrote; Craxton drew and painted and Joan Leigh Fermor charted a blissful interlude in evocative photographs. Craxton and Fonteyn were briefly lovers and lasting friends.

Craxton wall lamps like these were designed for the Athens home of Maro and George Seferis around 1960. A double-tailed mermaid was the poet's personal symbol.

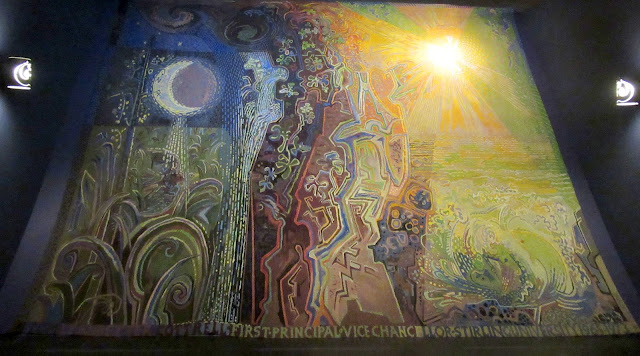

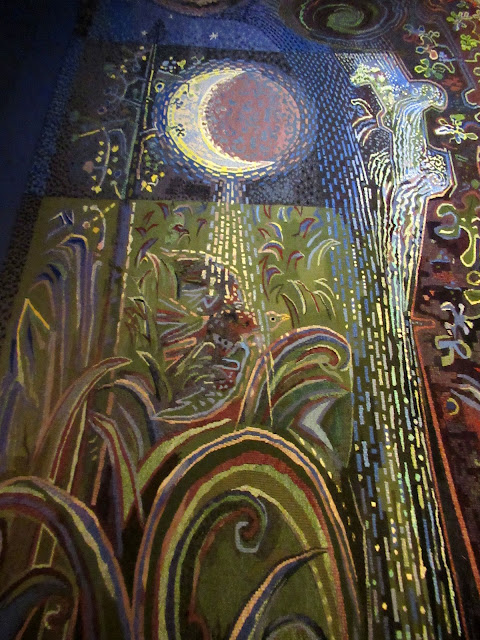

Landscape with the Elements, 1975-76, (tapestry)

After he was exiled from Greece during the time of the dictatorship, Craxton landed in Edinburgh where he was invited to design and oversee a tapestry to be produced by Dovecot Weavers in honour of the University of Stirling pioneer Tom Cottrell, whose death made the project an epitaph. The resulting Craxton composition, titled Landscape with the Elements, is a tribute to traditional Cretan weaving and to the mythology, climate, scenery and sensuality of Greece. Although using the full palette of 500 coloured threads, the tone is both vivid and mournful. A striking study in nostalgia.

looking closer

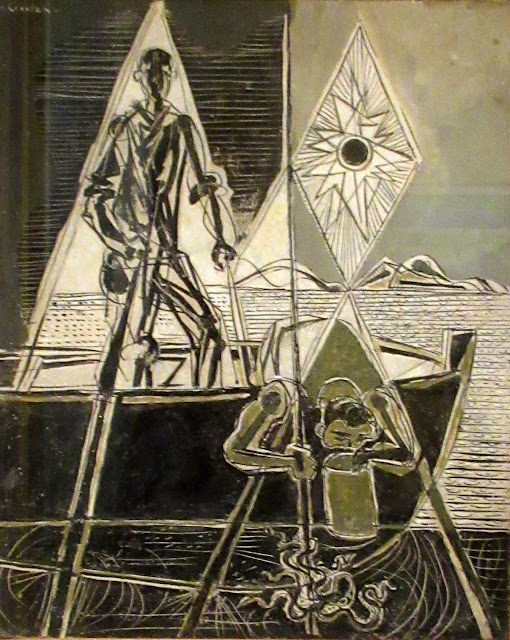

This masterpiece of linear colour from Hydra was abandoned as a failure after 15 years of struggle. Originally there were three figures, before one was removed. The energy of the octopus fisher contrasts with the supine figure possibly inspired by a maimed deep-sea diver.

Shepherd, 1984, (tempera on canvas)

Octopus Fishermen, 1953, (oil and ink on board)

The Butcher, 1964-66, (oil on canvas)

In 1947 Craxton visited Crete for the first time - to see Knossos, trace El Greco's birthplace and a follow a demobbed butcher home to Herakleion.

A former sailor danced the zeibekiko below the Minoan palace, with a backflip over an upturned chair. Craxton spotted the connection with the bull-leaping fresco of Knossos and a folk survival spanning 4,000 years. This merging of past and present was echoed in his Greek-inspired designs for the 1951 Covent Garden ballet Daphnis and Chloe in London.

No comments:

Post a Comment