'I have a need which gives birth to a hope. That, at some point, all those who stood in front of me in the psychiatric institutions will stand next to me on the street. That we can all live without the stigma of the 'Psy' imprinted on our foreheads. That we can live with dignity, solidarity and humanity'.

Franco Basaglia (Italian psychiatrist, neurologist and professor, instigator of Law 180/19898, which established the reform and abolition of psychiatric institutions in Italy).

A photographic exploration of mental illness and its treatment in mental health institutions, by Theodoris Nikolaou, journalist and photographer.

The exhibition consists of nine visual chapters, including the photographer's own personal experience, in which he attempts to help us get to know those who we might see as 'other' - through images which could ultimately represent any of us.

For the last five years Nikolaou has been systematically visiting psychiatric hospitals all over Greece, investigating a fragmented public mental health system, recording the contradictions, the personal dead ends, the stigmatisation, and the social exclusion that it generates. But, he does not stop there; he is not only interested in darkness. His work also includes lifer after institutionalisation in community reintegration and psychosocial rehabilitation programs.

'I was first diagnosed with depression in 2008. For years I have been unable to perform any work or social action. My depressive episodes are always accompanied by depersonalisation - derealisation. It's like I don't have a past; neither a present or future. I perceive myself as a non-other: the world, sometimes as if it does not exist and sometimes as if I do not exist within it.

I started photographing out of necessity, in a state of terror. Because the photographic act is proof in itself that the world exists. Thus, I, who press the shutter button, am included as a living cell in it. I keep on photographing with this condition always in mind. I hope that I will not forget over the years. I don't want to write about regiments, protocols and treatments. Besides, writing hurts. Here is another function of photography: to ease the pain, to offer a soothing balm to the mind. In these images, anyone can project anything they wish. For me, along with everything there is in this room, they are my life. The womb that gave birth to my few-months-old daughter, my partner, my mother and father, the sperm and the egg. The working-class house where I was born, the way I suffered and the place where I was healed...

I want to believe that the people involved in this project saw in me not just a photographer, but someone to whom they fearlessly entrusted and reposed their universal human story. Someone who will take it beyond the borders of their world - internal and external. This is my reward. For this I owe them profound and eternal gratitude'.

The reconstruction of the self:

'The sense of loss of the self and the effort to reconstruct it is one of the dominant features of mental disorder'.

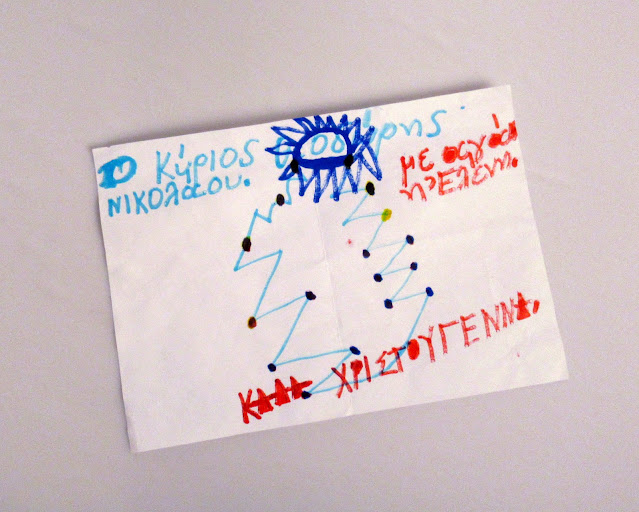

A patient's notes from the [notorious] psychiatric hospital of Leros.

Photos of a psychiatric institution (Leros):

Leros, one of the Greek islands in the Aegean, has become infamous worldwide because of its mental institution, which provoked universal outrage in the 1980s. The Leros asylum was established in 1958, taking the official name Colony for Psychopaths, in order to take residents of other psychiatric asylums in Greece. In a country that was experiencing the disastrous aftermath of WWII and the Civil War, socioeconomic and political circumstances created conditions for the reinforcement of the asylum structure and a dramatic increase in the number of institutionalised patients in public mental hospitals.

Most patients were transferred to Leros en masse from other asylums without prior notice. In total, 4000 psychiatric patients were moved. The referrals to Leros were either with the consent of mental health professionals or covered up. In 1982 all referrals to Leros stopped.

In 1989, the UK Observer published an article on Leros, presenting the appalling conditions in which the patients lived there. Residents suffered severe deprivation, extreme institutionalisation and violation of basic human rights. International pressure on the asylum then escalated and and mental health professionals called for immediate action. Eventually, it was the Leros case that triggered the process of reform of Greek mental health institutions and in the early 1990s the first psychosocial rehabilitation and reintegration structures were created.

Giorgos Ioannidis arrived in Leros in 1990, to work as the manager of the asylum: his aim was to reform the hospital. 'When I arrived, the hospital looked like a concentration camp. More than a thousand patients were guarded naked by fishermen and shepherds, while only one psychiatrist worked in the centre', Ioannidis told Euronews. 'At the same time, the hospital's terrible living conditions affected the locals working there. Leros was the island with the highest rate of alcoholism'.

Fast forward to 2021, and the spectre of detention still hands over Leros. Around 200 asylum seekers live in prefabricated buildings with the grizzly facade of the abandoned hospital looking over them from the rear. So, since the end of WWII, the island has in many ways been a detention centre.

Amulets:

'A cross, a hair band, an old children's toy. A small box with a stone inside: its owner, Fotis, likes to hear the metallic sound as he shakes it thousands of times a day. Everyday objects, expendable, almost unimportant to most of us.... These objects symbolise the human effort to exist, to acquire roots and property. Thus, the nature of these objects is altered by means of necessity. They turn into amulets... The collection of these objects started, not on my own initiative, but at the request of the people in the psychiatric hospitals and rehabilitation facilities that I keep something of theirs. The anxiety that they offer them to me so that I won't forget them, even today, is overwhelming'.

News of America:

Mr Kostas is 84 years old. In 1991, after 25 years in the psychiatric institution of Leros, he returned to the island of Evia, where he was originally from. He will be one of the first guests of the EPEPSY guesthouse in Chalkida, one of the first psychosocial rehabilitation and reintegration facilities to start operating within the framework of deinstitutionalisation. He lives there to this day, enjoying everything he was deprived of on the Aegean island. I have been visiting Mr Kostas for the past five years. I will find him sitting cross-legged in the living room or in the dining room filling notebooks with his words.,, If someone asks him what these pages contain, he will answer that these notebooks are 'news from America'....

Mr Kostas' letters and drawings, all perfectly aligned and not haphazardly placed, to some may be nothing more than another symptom of his disorder. For some it may be a way, obviously obsessive-compulsive, to pass his time in the guesthouse. But if we look beyond the writing and behind the words, it is quite possible that we'll see in these notebooks his Sisyphean effort, which in itself is capable of filling up his soul'.

List of the names and photographs of the people involved in the project:

Days out:

It was in the early 1990s when the first psychosocial rehabilitation and reintegration structures were created in Greece, as a result of the denunciations and international outcry over what was termed 'the national shame' of Leros.

Today, hundreds of people reside in the reintegration and psychosocial rehabilitation facilities in Greece, who, in complete contrast to the social isolation and institutionalisation of Leros, have the opportunity to fall in love, travel and participate in groups within the community.

Unlike the previous photographs, these are in colour.

'There is a certain kind of writing, some drawings and shapes that have a short life expectancy. They are found on the walls of the psychiatric institutions and their existence is at the disposal of the cleaning lady who will remove them.

Many times, the imprint of a person in pain is stronger than their presence, their echo louder than their own cry. In the country's psychiatric institutions, the site where the self is 'extinct', in-patients are trying to discover not only how to get on their feet, but also how to be heard....[The in-patients] write and paint not for their own posterity, but because through this process they suggest something fundamental: that by writing and drawing they continue to exist.

Why do I photograph the walls in psychiatric hospitals? ... To expose to us something that is not seen, to carry into the future something that does not exist. As we flip through it, we become mediators of a voice, crying out to be heard'.

A book on a table full of photographs of what was found on the walls of psychiatric institutions.

This is a paraphrase of the rallying cry of the Greek revolution against the Turks, which was: better to have one hour of freedom than forty years of slavery.

We should obliterate those who swat us away as if we were flies

I am glad you enjoyed reading this. Thank you.

ReplyDelete