Neo-Impressionism in the Colours of the Mediterranean at the Goulandris Foundation, Athens.

Neo-Impressionism, or Divisionism, also called chromoluminarism, is the characteristic style of painting defined by the separation of colours into individual dots or patches that interact optically. This exhibition is dedicated to the Mediterranean years of the Neo-Impressionists. It follows the artistic development of Signac, Cross, Luce and Van Rysselberghe towards a freer and bolder style of painting. The palette of these artists, enamoured of pure colours, continually gains in vigour and vicaciousness. As such, it illustrates in the most elegant way possible the words of authors who had ventured before the painters into this little-frequented Mediterranean coastline: Guy de Maupassant, Stendhal, Theodore de Banville. Initially prized by people suffering from poor mental health, the Mediterranean climate attracts increasingly greater numbers of art lovers who are enticed by a genre of painting that is from that time on solidly rooted in the sensory and the subjective.

Signac and Cross remain faithful to the Neo-Impressionist technique to the end of their days, but Luce and Van Rysselberghe will gradually distance themselves. Newcomers like Matisse, Manguin will experiment with the divided brushstroke quite diligently, with an independent spirit that anticipates the artistic revolutions to come.

On March 29, 1891, Georges Seurat dies unexpectedly at the age of 31. The death of the founder of Neo-Impressionism leaves the other members of the group - in particular, Paul Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, Maximilien Luce and Theo Van Rysselberghe - at a loss. Many critics and painter friends, including Camille Pissarro, foresee an imminent end to the artistic movement which they misinterpret as nothing more than a transient rebellious offshoot of Impressionism.

However, Seurat's death marks only the closing of the first chapter of Neo-Impressionism. A second chapter will soon unfold, far from Paris, on the shore of the Mediterranean. And, Signac, now the leader of the group, takes it towards new horizons, both geographic and artistic.

1. Reborn on the shores of the Mediterranean.

Cross is the first to discover the Mediterranean in 1883. In search of an isolated spot spared of industrialisation and tourism, he settles in Cabasson near Le Lavandou in 1891, then moves to Sait-Clair for good. Signac, who intends to leave Paris for part of the year, follows him in 1892 and chooses Saint-Tropez, a small fishing harbour still unknown at that time and situated nearby. The two painters' wonderment at the untouched nature of the Midi is such that they waste no time in convincing their friends Luce and Van Rysselberghe to come and join them for summer holidays that promise to be both inspiring and relaxing.

The works produced during the first Mediterranean period reveal a group of artists who are eager to pursue the Neo-Impressionist adventure despite the difficulties and criticisms. Each one in his own manner distances himself from Seurat's dogma to let explode on the canvas a growingly more subjective style of painting. In this way they allow Divisionism to rid itself of its excessively rigorous tendencies and to blossom with an unequalled vigour.

Henri-Edmond Cross, Portrait of a Young Man, 1885-89, (oil on canvas)

Paul Signac, Saint-Tropez, Sun Setting over the City, 1892, (oil on wood)

Paul Signac, Chromatic scale tests, 1892

These two panels detail the implementation, by Signac, of the scientific theories that led him to follow Seurat in the venture of Neo-Impressionism. More particularly, they were both inspired by the chromatic circles of Michel Eugene Chevreul, director of the Gobelins Manufactory, who sought to create a universal classification of colours. Rather than working in a circle, an ineffective method for practical use, Signac outlined small rectangles, most of the same size, in pencil. Then, he placed adjacent colours of the spectrum side by side and gradually degraded them with white. The desired colour would then be recomposed on the canvas, by association and juxtaposition of these small touches of adjacent colours of the spectrum. The optical mixing would be carried out unconsciously by the eye, at a certain distance.

Henri-Edmond Cross, Study for Beach at Cabasson, 1891-92, (oil on canvas)

Paul Signac, Study for In the Time of Harmony, Standing Boules player, 1894, (oil on wood)

Theo Van Rysselberghe, Coastal Scene, 1892, (oil on canvas)

Van Rysselberghe coated his canvasses with a softer palette than his colleagues, playing with contrasts more subtly than them. He was thus able to breathe all his subjectivity into his canvas, while remaining faithful to the constraints of division.

Paul Signac, Saint Tropez. After the Storm, 1895, (oil on canvas)

Three years after discovering the Midi, Signac allows a new vision of Neo-Impressionist technique to flourish on the canvas. The dots broaden out to become tesserae. This marks the pivotal transition towards the advent of a more subjective style, eager to reintroduce all the charms of the ephemeral that the Impressionists commanded so masterfully.

Henri-Edmond Cross, The Farm (evening), 1892-93, (oil on canvas)

Henri-Edmond Cross, Nocturne, 1896, (oil on canvas)

looking closer

Maximilien Luce, The Port of Saint-Tropez, 1893, (oil on canvas)

Tranquillity, softness and serenity.

Maximilien Luce, Saint-Tropez. Citadel Hill, 1892, (oil on canvas)

Theo Van Rysselberghe, Paul Signac at the helm of the Olympia, 1896, (oil on canvas)

Maximilien Luce, Saint-Tropez, The Cenetery Road, 1892, (oil on canvas)

looking closer

The divisionist technique seems to correspond entirely to Luce's need to patiently, carefully render the smallest detail. The seven colours of the spectrum, scattered throughout the composition, are so skilfully applied that Luce faithfully renders the rocks and the path without ever using the 'useless ochre and earth colours' which Signac and, before him, Delacroix detested.

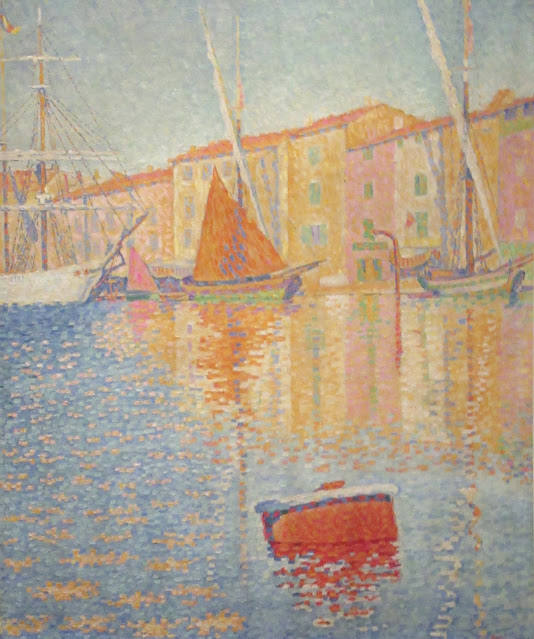

Paul Signac, The Red Buoy, 1895, (oil on canvas)

Paul Signac, Saint-Tropez. The Fountain of Lices, 1895, (oil on canvas)

No comments:

Post a Comment