In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s

at the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Ukraine has been divided between various empires for centuries, but periods of sovereignty in the country's history contributed to the development of a distinct identity, which in the 19th century became consolidated into a national consciousness advocated by artists and thinkers. Such a complex history produced a particular cultural profile, born from the fusion of Ukrainian, Polish, Russian and Jewish comunities.

Modernism in Ukraine unfolded against a complicated sociopolitical backdrop: WWI, the collapse of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian People's Republic and the subsequent absorption of the Ukrainian lands by the Soviet Union. Yet despite such political turmoil, this became a period of true flourishing in the Ukrainian arts. The exhibition tells the story of modernist artists and the visual experiments through which they sought to renew Ukraine's culture and autonomy.

Cubo-Futurism:

At the turn of the 20th century, when the Ukrainian lands were divided between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, no Ukrainian city was allowed to have its own art academy. This compelled aspiring artists to move elsewhere to complete their studies. Those from Russia-controlled Ukraine initially graduated mainly from the Imperial Academy in St Petersburg, but increasingly their focus shifted to European capitals such as Munich, Paris.

Inspired by the radical trends they encountered in these cities, young artists from Ukraine began experimenting with a new visual language that combined elements of Cubism, with its geometrisation and fragmentation of the picture plane, and Futurism, characterised by vehement energy and movement. Consequently, art created in Ukraine featured dynamic compositions and simplified forms with a gradual move towards abstraction. At the same time, artists adopted vivid colour and rhythmic compositions of Ukrainian folk and decorative art. Such references to Ukrainian imagery are also visible in the art of the emigre artists who developed their careers abroad.

Oleksandr Bohomazov, Landscape, Locomotive, 1914-15

In his paintings, Bohomazov created a world in constant motion using an increasingly abstracted visual language.

Alexandra Exter, Three Female Figures, 1909-10

Oleksandr Bohomazov, Landscape, Caucasus, 1915

Alexandra Exter, Bridge (Sevres), 1912

Alexandra Exter, Composition (Genova), 1912

Vladym Weller, Composition, 1909-20

Sonia Delaunay, Simultaneous Contrasts, 1913

Volodymyr Burliuk, Ukrainian Peasant Woman, 1910-11 (oil on canvas)

Alexander Archipeniko, Flat Torso, 1914, (bronze and marble)

Theatre Design:

In the late 1910s, Ukraine witnessed a revolution in theatre productions thanks to the combined talents of experimental writers, directors and stage designers. This transformation took place against the backdrop of Ukraine's fight for sovereignthy: the proclamation of the Ukrainian People's Republic (1917-18) and the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-21) fought against, amongst others, the invading Russian Bolsheviks, who sought to integrate Ukraine into their Soviet state.

Two names stand out as catalysts of this revolutionary shift in theatre: Alexandra Exter and Les Kurbas. Exter's pioneering theatre designs translated Cubist and Futurist principles into scenography. In 1918, she opened a private studio in Kyiv with a separate course on stage design. Among her students were some of the most acclaimed theatre designers of the next generation including Anatol Petryskyi and Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khmostov. As a theatre director, Kurbas introduced a modern European repertoire to his productions, first in Kyiv and later in Kharkiv. He engaged the most experimental artists as scenographers to explore the creative intersections between progressive art trends and the revival of native traditions.

Alexandra Exter, Costume design for the Greeks in the play 'Famira Kifared' at the Chamber Theatre, Moscow, 1916

Vadym Meller, Costume design for the play 'Mazepa' at the First Taras Shevchenko State Theatre, Kyiv, 1920

Vadym Meller, Sketch of the 'Masks' choreography for Bronislava Nijiiska's School of Movement, Kyiv, 1919

Vadym MellerVadym Meller, Costume design for the Friar in the play 'Mazepa' at the First Taras Schechenko State Theatre, Kyiv, 1929

Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khvostov, Costume design for the Soldier in the opera 'Love for Three Oranges'. Unrealised production, 1926

Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khvostov, Costume design for two Guards in the opera 'Love for Three Oranges'. Unrealied production, 1926

Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khovostov, Costume design for the Soldier in the opera 'Love for Three Oranges. Unrealised production, 1926.

Kultur Lige:

The organisation Kultur Lige (the Cultural League) was founded in Kyiv in 1918 to promote the development of contemporary Jewish-Yiddish culture. It operated within a unique sociopolitical context shaped by the independent Ukrainian People's Republic, led by the short-lived government of the Central Rada (Council) that recognised the multicultural and multilingual nature of Ukraine's society. Despite these efforts, multiple vying parties in the Ukrainian War of Independence perpetrated violent pogroms against Jewish communities during the years 1918-21.

The Kultur Lige's art section united young Jewish artists from Kyiv and many other cities. They sought a synthesis of Jewish artistic tradition with the achievements of the European avant-garde. The Kultur Lige ceased to exist by the mid-1920s, following growing pressure from the Soviet regime.

El Lissitzky, Composition, 1918-1029, (oil on canvas)

Sarah Shor, Sunrise, 1910s, (oil on canvas)

Sarah Shor, Horse Riders, 19102, (gouache and pastels on paper)

Issakhar Ber Rynack, City, 1917, (oil on canvas)

Marko Epshtein, Woman with Buckets, 1920, (Indian ink, lead pencil and watercolour on paper pasted on cardboard)

Marko Epshtein, The Tailor's Family, 1920, (Indian ink and watercolour on paper, pasted on cardboard)

Marko Epshtein, Cellist, 1920

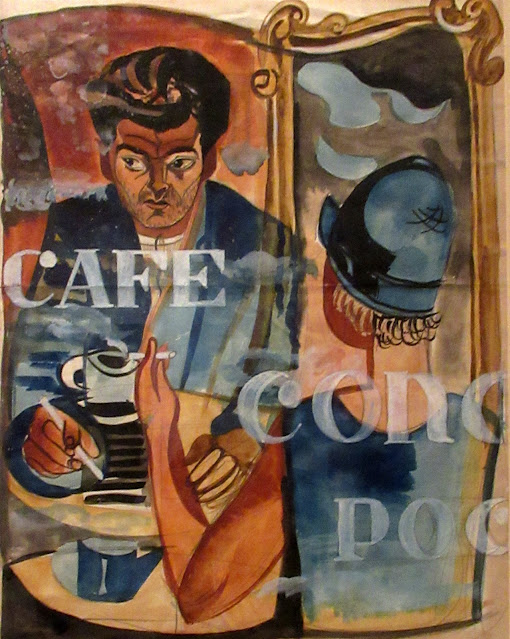

Anatol Petrytskyi, At the Table, 1926, (oil on canvas)Ukraine under the Soviets:

After nearly five years of the bloody Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-21), the Bolshevik Red Army defeated the national Ukranian forces, and the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic was established with Kharkiv as its capital. In 1923, the Soviet authorities introduced the policy known as Ukrainizatsiia (Ukrainisation), an ideological concession to appease local national sentiment. This policy allowed for a level of cultural autonomy in the Republic, facilitating the develoment of the Ukrainian language and culture. For the next decade, Ukrainian intelligentsia participated in the ambitious project of creating a new cultural identity that was both Ukrainian and Soviet.

During this period, Mykhailo Boichuk's studio of monumental art emerged as the leading artistic group in Soviet Ukraine. Its members, known as the Boichukists, completed state commissions to create murals for public spaces and buildings. The school was short-lived however. Labelled 'Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists', Boichuk and a close circle of his associates were executed during the Stalinist purges of the 1930s, with most of their public art subsequently destroyed.

Mykola Kasperovych, Ducks, 1920s

Mykola Kasperovych, Portrait of a Girl, 1920s

Ivan Radalka, Photographer, 1927, (tempera on paper)

Tymofii Boichuk, Women Under the Apple Tree, 1920, (tempera on cardboard)

Vasyl Vermilov, Self-Portrait, 1922, (oil and metal on wood relief)

Vasul Yermilov, Journal cover design for 'Avanhard' (Avant-garde), 1929, (Indian ink and gouache on paper)

Vasyl Yermilov, Journal cover design for 'Nove Mystetstvo' (New Art), 1927, (Indian ink and gouache on paper)

Anatol Petrytskyi, Portrait of Mykhail Semenko, 1929, (watercolour, lead pencil and ink on paper)

Anatol Petrytskyi, Constructivist Composition, 1923, (oil on canvas)

Mykhailo Boichuk, Dairy Maid, 1922-23, (tempera on canvas)Kyiv Art Institute:

The development of the visual arts in Ukraine in the 1920s was intimately linked to the Kyiv Art Institute. This was the successor to the Ukrainian Academy of Art, the first institution of higher art education in Ukraine, founded when the country proclaimed its independence during the period 1917-18. In 1924, to conform to the Soviet system of higher education, the Academy was restructured into the Kyiv Art Institute. With a modern curriculum, including contemporary subjects such as industrial design, the Institute became of the USSR's leading art schools. It also hired new instructors from across the Soviet Union, with such progressive artists as Kaztmyr Melevych and Vladimir Tatlin joining its faculty.

Viktor Palmov, The 1st of May, 1929, (oil on canvas)

Viktor Palmov, Group Portrait, 1920-21, (oil on canvas)

Vasyl Sedliar, Portrait of Oksana Pavlenko, 1926-27, (tempera on canvas)

Anatol Petrytskyi, The Invalids, 1924, (oil on canvas)

Kazymyr Malevych, Sketch of the painting for the conference hall of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, Kyiv, 1930

at the back of the sketch

Kazymyr Malevych, Landscape (Winter), after 1927, (oil on canvas)

Born in Kyiv into a Polish famly, Kazymyr Malevych grew up in the Ukrainian countryside and became accustomed to local folk traditions. In 1933, while residing in Russia, Malevych began working with a new artistic approach known as Suprematism: a style that forgoes any reference to natural forms in favour of an abstract visual language to express feelings and spirituality. He returned to Ukraine in 1929 to teach at the Kyiv Art Institute. Around this time, he abandoed abstraction to focus on a more figurative style, as seen here.

Oleksandr Bohomazov, Experimental Still-Life, 1927-28, (watercolour on paper)

Oleksandr Bohomazov, Sharpening the Saws, 1927, (oil on canvas)

The last generation:

The last generation of Ukrainian modernists matured in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Mainly graduates of the Kyiv Art Institute, these artists were fascinated with internaional art movements, such as New Objectivity and Italian Novecento, but their artistic activity was cut short by a radical change in the political climate. Art was increasingly viewed through the prism of 'class consciousness' and Soviet subject matter came to dominate all spheres of artistic output. Betwen 1932, and 1934, Socialist Realism was introduced as the only official artistic style to be practised in the Soviet Union, effectivelly ending modernist experimentation.

Kostiantyn Yeleva, Portrait, late 1920s, (oil on canvas)

Oleksandr Syrotenko, Rest, 1927, (oil on canvas)

Semen Yoffe, In the Shooting Gallery, 1932, (oil on canvas)

Postscript:

The policy of Ukrainizatsiia was curtailed in the 1930s amidst purges of the Ukrainian intelligentsia. Hundreds of writers, theatre directors and artists, including Mukhailo Boichuk, Mykola Kasperovych, Les Kurbas, Ivan Padalka, Mykhail Semenko and Vasyl Sediar, were labelled as 'bourgeois nationalists' and executed. Many more were imprisoned and sent to labour camps. Manuscripts, books and artworks were destroyed. Murals were overpainted or scraped off walls. Canvases that were not destroyed were sent to secret repositories.

In the 1960s and 1970s Western countries rediscovered the revolutionary art of the late Russian Empire and early Soviet period. Since then, artists born or living in Ukraine have been considered under the catch-all mono-ethnic term 'Russian avant-garde', yet their artistic experimentation was integral to the development of Ukrainian culture.

This exhibition has been extremely helpful in correcting this historical oversight, highlighting for me the complicated and little-known story of modernism in Ukraine, as well as its many links to European culture. The current invasion of the country by Russia is yet another chapter in the history of this country that has been through so much.

No comments:

Post a Comment