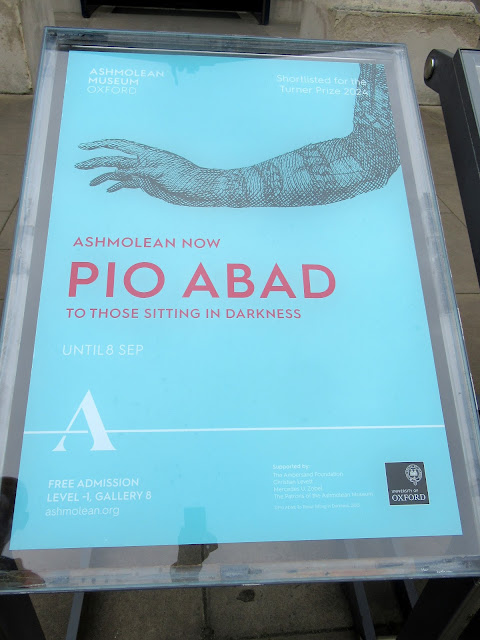

To Those Sitting in Darkness, by Pio Abad

at the Ashmolean, Oxford.

An interesting exhibition and very different to what is usually exhibited in museums and galleries.

New drawings and objects by London-based artist Pio Abad. The title 'To Those Sitting in Darkness' is a reference to American writer Mark Twain's satire 'To the Person Sitting in Darkness' which strongly criticised imperialism. Deeply informed by the history of the world and particularly the Philippines, where Abad was born and raised, his works draw out transnational lines between historical incidents and people, and our lives today. Concerned with colonial history and cultural loss, Abad's works are exhibited together with select works by other artists and 'diasporic' objects chosen by the artist.

Abad views the exhibition as 'an act of illumination that puts unexamined histories on display and addresses objects that have been confined to the margins of story-telling'. Representing the artist's own voice, the commentary on each piece adds an important narrative layer to his visual work.

When I was invited by the Ashmolean, Villa's act of defiant re-construction in the face of immeasurable cultural loss was an important starting point.

Giolo's Lament traverses his tattooed hand through engravings arranged on the walls like a musical score. A spectral limb grasping for something out of reach, perhaps reading out for a body lost at sea. Inscribed on pink marble, Giolo is at once monoment and flesh, etching the forgotten man into permanence but also reminding us of his fragile humanity. In freeing Giolo from the archives, I wanted to portray him as a trafficked body and a grieving son, not a specimen of curiosity.

Bladed Weaponry from Mindanao, 19th century

Carlos Villa, 1971

This portrait By Filipino American artist Carlos Villa looks to ethnographic imagery as a way of linking the past with the present. An Itek print is covered with ink designs on Villa's face, suggesting the tatooing culture prevalent in Pacific Islander cultures. While the facial marks are the artist's own design, the motifs reference transoceanic cultures, from Aotearoa to the Philippines, Hawaii to the American Pacific Northwest. This work has become emblematic of Villa's celebration of the self as a product of syncretic solidarities.

When I was invited by the Ashmolean, Villa's act of defiant re-construction in the face of immeasurable cultural loss was an important starting point.

Pio Abad, Giolo's Lament, 2023

This work is based on an etching by John Savage. Reading an account of Giolo's life, a passage about his journey to England struck me: 'This Indian prince was taken prisoner by an English man of war, as he and his mother were going out upon the sea in a pleasure-boat. His mother died on ship-board; at which the prince, her son, showed abundance of concern and sorrow.

The most recurrent object from the Philipines in museum collections is the bladed weapon from Mindanao, where indigenous tribes adapted Islam into their belief system. The founding collection of the Pitt Rivers Museums included kris swords, wavy dougle-edged weapons with precious handles. They were made for individual warriors carrying a spiritual potency bestowed upon its owner. Most of them were gathered during the Philippine-American War in the early 20th century, when American colonisers waged asymmetric battles against the Moros, the local Muslim population in Mindanao. Since the arrival of the Spanish on Philippine soil, the indigenous Mindanao people have waged a seccessionist struggle against a national government that has inherited the dehumanised depiction of Moros from their colonisers. The very categorisation of Moro weaponry as Philipine artefacts could be considered as an act of violence, appending them to a national category that they have resisted. Here, Moro weapons from the Pitt Rivers collection are exhibited for the first time since accession.

Sinaglata, Woven fabrics, 2017

The Moro swords encounter contemporary fabrics from Mindanao. Outside the Philippines, little is known about the siege of Marawi in 2017, when the national government under then President Rodrigo Duterte, aided by the American military, rained bombs on the northwestern Mindanao city of Marawi, in a quest to capture a militant group affiliated with the Islamic State. The conflict levelled the entire city and devastated hundreds of thousands of lives. Sinagtala is a community of weavers built on the ashes of this under-reported war. Established by Jamela Alindogan, a journalist covering thesiege, Sinagtala (starlight in English) supports displaced women, who wove as the bombs fell. The jagged motifs on the traditional fabric represent the tremors that reverberated around the weavers. Amidst the inhumanity of war, the loom became their site of refuge, their grief woven ferociously into colour and pattern.

Pio Abad, 1897.76.36.18.6, 2003

I came across a startling discovery, reading Dan Hick's book The Brutish Museum. My flat is located in what used to be the Great Stores of the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich. In preparation for the punitive Benin expedition in February 1897, an act of retaliation to the killings of a small British delegation to the Kingdom a month earlier, the Grand Stores became the staging post for the British Army.

In these drawings, Benin bronzes from the British Museum are measured and arranged next to objects in my home. I want to find a non-empirical way of accounting for these stolen artefacts, tracing the narrative of dispossession according to personal and emotional dimensions. The title mimics the format of museum accession codes, linking the year of the raid with my address. Home becomes the site where shared histories of loss can be contemplated.

Pio Abad and Frances Wadsworth Jones, For the Sphinx, 2023, (bronze)

In the gardens of Blenheim Palace sit a pair of Sphinx sculptures bearing the likeness of Gladys Deacon, the Duchess of Marlborough, who lived in the palace during her tumultuous marriage to Charles Spencer-Churchill. I ended up in Blenheim after coming across a photograph of Deacon with a pearl and diamond diadem. This diadem, patterned after a traditional Russian folk headdress, was originallhy owned by the Romanov family. After their execution in 1918, the tiara was nationalised by the Bolshevik regime. On behalf of Joseph Stalin's government it was auctioned off by Christies in 1927 and acquired by Deacon.

My first glimpse of the Kokoshnik tiara, previously owned by Gladys Deacon, was during a press conference in Manila in 2016. It unexpectedly appeared as the centrepiece of a horde of jewellery that the government had confiscated from the Philippine kleptocrat Imelda Marcos. It seemed that Mrs Marcos had purchased the diadem shortly after Deacon's death in 1978. Today, the Kokoshnik is locked in the central bank vaults in Manila.

Here, the tiara appears as a pair of identical sculptures, reconstructed by my wife and collaborator, jeweller Frances Wadsworth Jones. Facing each other akin to the Blenheim sphinxes, the diadems bear witness to each other, their outrageous provenance and recurrence in history, turning them into intimate testimonies to endless cycles of violence, upheaeval and impunity.

George Le Clerc Egerton, Sacrificial Altar, Benin, 1897

Here, the tiara appears as a pair of identical sculptures, reconstructed by my wife and collaborator, jeweller Frances Wadsworth Jones. Facing each other akin to the Blenheim sphinxes, the diadems bear witness to each other, their outrageous provenance and recurrence in history, turning them into intimate testimonies to endless cycles of violence, upheaeval and impunity.

George Le Clerc Egerton was the chief of staff of the 1897 Benin expedition. He kept a journal of the raid with each page beginning with heading 'Orders for Tomorrow' - imperial plunder reduced to a banal language of British bureaucracy. As it approaches the 18th of February, the violent climax of the expedition, the diary gets increasingly stained, the pages bearing the residue of an entire city set ablaze, its people decimated, and the bronzes looted.

Alongside the journal, Egerton produced a watercolour depicting a scenely shortly after the attack: a Benin altar with eight bronze heads and three ceremonial bells arranged in a row, lying on what appear to be pools of blood. Forty three of the Benin bronzes in the collection of the Pit Rivers Museum are on loan from the Le Clerc Egerton Trust.

No comments:

Post a Comment