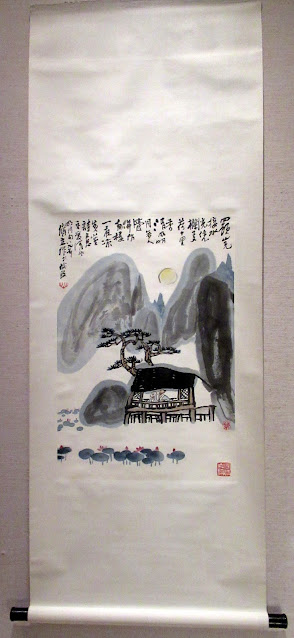

In stark contrast to the secular man (probably the artist himself) and man in the painting, the inscription that fills up the space is taken from Buddhist scriptures, a common element in Li Jin's work. The lasting concern for and interest in Buddhist throught in his works demonstrates the significant impact of his sojourns in Tibet in his art, while alighing with his chosen approach and subjects, which emphasise the significance of 'being present' even in the most 'insignificant' day practices.

Sunday, 24 November 2024

Li Jin - Simple Pleasures

In stark contrast to the secular man (probably the artist himself) and man in the painting, the inscription that fills up the space is taken from Buddhist scriptures, a common element in Li Jin's work. The lasting concern for and interest in Buddhist throught in his works demonstrates the significant impact of his sojourns in Tibet in his art, while alighing with his chosen approach and subjects, which emphasise the significance of 'being present' even in the most 'insignificant' day practices.

Tuesday, 12 December 2023

Fang Lijun - Portraits and Porcelain

Fang Lijun - Portraits and Porcelain at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

The motif that runs through all his work, from student sketches to complex, delicate porcelains, is that of the human head. While Fang's bald, expressionless faces in the 1990s symbolised the universal ennui of a politically controlled society, his recent works are personal portraits of friends, family, colleagues and acquaintances from throughout his life. In porcelain he challenges not the society around him but rather the precariousness of the material itself.

Two Figures, (series 1, no. 5), 1991, (oil on canvas)

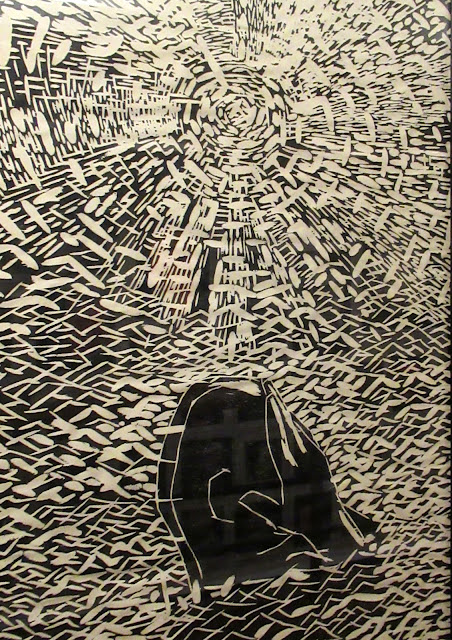

Swimmer, 1998, (woodcut print on paper) (apologies for the reflections on the head)

A lone swimmer is a subject Lijun chose frequently throughout the 1990s, and one of his best-known works of the period shows a single figure standing in an intensely blue pool. Many of his swimmers, inclucing the work shown here, appear to be self-portraits. Lijun suffered a fear of water as a child, only learning to swim after he had moved to Beijing as a student.

Untitled, 1998, (oil on canvas)

From the mid-1990s for around a decade, Lijun's depictions of people became more colourful, with subjects that often turned towards nature rather than away from society. The combination here of a head, baby-like figures and small flowers, all in strong colours, is typical of this period.

Mr Li, 1998, (oil on canvas)

This painting is after an image or occasion from some years prior to its production. It depicts the art critic Li Xianting, a longtime friend of Fang Lijun who gave the name 'Cynical Realism' to the rebellious art movement of the 1990s in which Lijun became the leading figure. The painting stands apart from many of his depictions of swimmers in its use of monochrome oils, and the vivid actions of both the swimmer and the water.

Heads, 2016, (oil on canvas)

This image of multiple heads, shaven and viewed from the back, brings together elements common to much of Lihum's work from the 1990s onwards. The strong colours and golden look suggest some of the optimism of other works he produced during the late 1990s that included figures and flowers against strongly coloured skies, or the gold and orange swimmer paintings of the same period.

Porcelain, 2023

Lijun is interested in exploring the limits of the porcelain, and in this work he has created an exceptionally thin, delicate piece constructed around a matrix that burnt away in the kiln.

In the centre is embedded a modelled head, the subject that has featured in his works on paper throughout his life.

Porcelain, 2023

This structure is the result of several thousand experiments in small pieces, shown below. Part of its stability relative to other works comes from the use of a slightly thicker porcelain layer. The head embedded in the centre continues the use of the image that runs through his work from the 1980s onwards.