In the early 1970s, women were second-class citizens. The Equal Pay Act wouldn't be enacted until 1975. There were no statutory maternity rights or any sex-discrimination protecton in law. Married women were legal dependants of their husbands, and men had the right to have sex with their wives, with or without consent. There were no domestic violence shelters or rape crisis units. For many women, their multiple intersecting identities led to further inequality. The 1965 Race Relations Act had made racial discrimination an offence but did nothing to address systemic racism. The 1970 Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act gave people with disabilities the right to equal access but failed to make discrimination unlawful. In 1967, the Sexual Offences Act had partially decriminalised sex between two men, but lesbian rights were almost entirely absent from public discourse.In 1970 more than 500 women attended the first of a series of national women's liberation conferences. Sally Alexander, one of the organisers, notes it was the beginning of 'a spontaneous, iconoclastic movement whose impulse and demands reached far beyond its estimated 20 thousand activists'. Many of these activists were also members of organisations like the Gay Liberation Front and Brixton Black Women's Group. Together they marked a 'second wave' of feminist protest, emerging more than 50 years after women's suffrage. They understood that women's problems were political problems, caused by inequality and solved only through social change.

The artists in this room made art about their experiences and their oppression. They worked individually and in groups, sharing resources and ideas, and using DIY techniques. Their subject matter and practices became forms of revolt, and their art became part of their activism.

Maureen Scott, Mother and Child at Breaking Point, 1970, (oil on board)

In this painting, Scott depicts a mother staring out at the viewer while a child writhes and screams in her arms. It's an image of maternal ambivalence, the complex and contradictory emotions associated with motherhood, often grounded in the conflict between the needs of the parent and the child. By highlighting this widely experienced reality, Scott foregrounds the lived experience of many women.

The six demands

Women's march, 1971 (photo taken by Chandan Fraser)

The first UK women's liberation march was held in London in March 1971. Sheila Rowbotham, who was involved in the national women's liberation conferences was one of the organisers. The protest was attended by 4,000 women, men and children, demonstrating the significant interest in a national conversation on the rights of women. The mood of the march was uplifting and positive, with protestors playing the 1930's musical hit 'Keep Young and Beautiful' as an ironic call to arms.

Monica Sjoo, Phallic Culture, 1970, (oil, part on canvas, laid down on board)

Phallic Culture is a criticism of a society built on patriarchal structures in which men hold the power. It's an unusual painting for Sjoo as no women are included. In contrast to the colour and vitality of her depictions of women and the natural world, in this painting men build a grey rectangular city. An exaggerated phallus extends from the sky, dominating the image. To see more of Sjoo's work go here

Erica Rutherford, Red Stockings, 1970, (gouache on paper)

Erica Rutherford, The Bed, (acrylic on canvas)

Monica Sjoo, Wages for Housework, 1975, (oil on board)

Demanding recognition of unpaid domestic work, the Wages for Housework movement argued that capitalism was reliant on the free domestic labour of women, It encouraged visibility and acknowledgement of this labour as a way to combat oppression and help restructure social relations.

Jayaben Desai at the Grunwick Strike, 1976, (photograph taken by Sheila Gray)

Police at the Grunwick Photo Processing Lab strike, 1976, (photo taken by Val Wilmer)

Grunwick Photo Processing Lab Picket, 1976, (photo taken by Val Wilmer)

2. The Marxist wife still does the housework:

By the mid-1970s, women had asserted their right to equal pay and to work free from discrimination and harassment. Some held positions of power in business and politics, and following Margaret Thatcher's election as prime minister in 1979, a woman held the highest office in the country. Despite this, traditional gender roles remained. For women to achieve equality, change was needed in both public and private spheres.

Small consciousness-raising groups brought women together to discuss their shared experiences and recognise the social and political causes of their inequality. This practice woke women up to their oppression and made the personal political. Women discussed the concept of reproductive labour - the work required to sustain human life and raise future generations - and joined international campaigns such as Wages for Housework. Art became a tool to highlight the unpaid activities they were expected to perform and the physical and emotional impact this had on them.

For many women artists, there was no separation between their home and artistic practice. They produced work at kitchen tables between caring and domestic responsibilities. Their environment informed the materials used, the size and format of their work, as well as their subject matter. Artists also turned to their bodies as their subjects. They explored fertility, reproduction and the complexity of navigating highly prejudicial medical systems, particularly for women with multiple intersecting identities.

The artists in this section of the exhibition challenge art historical tropes and media stereotypes, from the idealised nude to the selfless mother and doting housewife. These women present their bodies and homes as sites of oppression while simultaneously reclaiming agency over them.

Many women see capitalism as the root of their oppression. They challenge its reliance on patriarchal systems in which men hold the power and women are largely excluded. They also view women's unpaid reproductive labour, a necessary condition of capitalism, as exploitation.

In the 1970s, many involved in the women's movement were looking for revolutionary change rather than reform and socialism provided answers. Women joined labour movements and trade unions, and set up Socialist and Marxist groups that focused on liberation for all. Yet outside of feminist organising, many anti-capitalist movements were accused of failing to acknowledfge the reality of gender inequality.

Robina Rose, Birth Rites, 1977

Birth Rites documents Julia Lauder giving birth at home surrounded by her family. The film focuses on women's agency during homebirth in contrast to some women's experiences in a hospital setting.

Janis Jefferies, Double Labia, 1980, (women construction, dyed sisal)

Most feminists got involved in at least one session of self-examination.

Loraine Leeson, Women Beware of Man Made Medicine. The Things That Make you Sick - East London Health Project, 1980

These posters were designed as 'visual pamphlets' for display in GP surgeries and other public places. They combine text with graphic layouts as a way of sharing information to local communities hit by cuts to NHS budgets in the late 1970s.

Rita McGurn, Untitled, 1975-84, (acrylic, wool and cotton yarns, stuffed with polyester hollow fibre)

Alexis Hunter, The Marxist's Wife (still does the housework), 1978

In this series of sequential images, a woman uses a cloth to clean a portrait of Karl Marx. The image features the words 'Man, Thinker, Revolutionary'. As the cloth passes over the word 'man' a smudge appears - a reference to Marx's failure to incorporate women's work in the home into his theory of labour relations. As Hunter states, 'women workers are invisible: they are absent from the analysis of the labour market on the one hand, and their domestic work and its exploitation is taken as given on the other'.

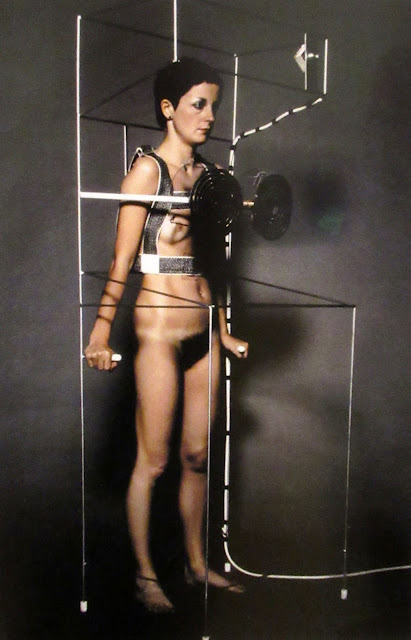

Helen Chadwicik, In the Kitchen, 1977

For this performance Chadwick created wearable sculptural objects from PVC 'skins'; stretched over metal frames. They included a cooker, sink, refrigerator, washing machine and cupboards. The original setting featured a strip of vinyl floor tiles and a soundtrack of excerpts from the BBC Radio 4 programmes Woman's Hour and You and Yours. Chadwick wrote: 'The kitchen must inevitably be seen as the archetypal female domain where the fetishism of the kitchen appliance reigns supreme. By highlighting and manipulating this familiar domestic milieu, I have attempted to express the conflict that exists between ... the manufactured consumer ideal/physical reality, plastic glamour images/banal routine, conditioned role-playing/individuality'.

Eileen Cooper, Figures on a Ladder, 1979, (charcoal and pastel on paper)

Elizabeth Radcliffe, Cool Bitch and Hot Dog, 1978, (wool, linen, papier mache, metal buckle and nylon glove on plywood, canvas and MDF)

Stella Dadzie, OWAAD Banner, 1978

OWAAD put the experiences of black and Asian women on the agenda of the UK's women's liberation movement. It began as an umbrella organisation connecting women's groujp like the Brixton Black Women's Group, Southall Black sisters and lots of others.

In the late 1970s it was rare to find a depiction of a home in the media or advertising that did not include a woman undertaking domestic and childcare duties. Despite the Sex Discrimination Act being passed in 1975, women needed a male guarantor to take out a mortgage or loan and were forced to rely on male partners and family members for domectic security. In the 1970s the average age of marriage for a woman was 24 and the average of new mothers was 26. Maternity leave was not legislated until 1975, and until 1990 only half of working women were eligible. Many women were forced to sacrifice their careers to raise children.

YBA Wife - Is There Life After Marriage? 1971

The YBA Wife campaign extended the 5th demand (legal and financial independence for married women) agreed at the 1974 National Women's Liberation Movement Conference. The campaign asked why women should becomes wives to begin with. Marriage vows, it was suggested, essentially amounted to little more than a job contract providing men with cheap childcare and domestic service. The print of this poster dates from 1981, the year of Prince Charles' wedding to Diana Spencer.

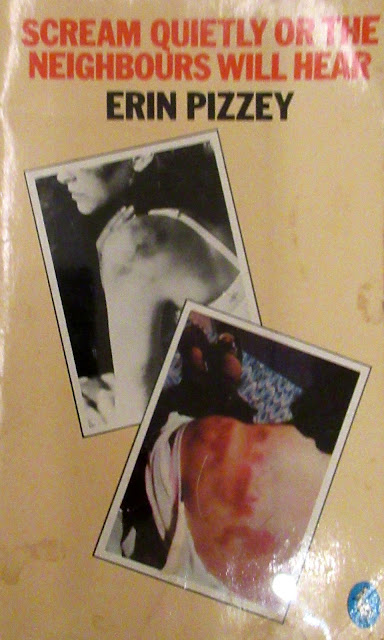

Christine Voge, Chiswick Women's Aid, 1978

Chiswick Women's Aid, founded in 1972, was one of the first refuges in the world for women and children escaping domestic violence, Evin Pizzey was a key organising figure at the refuge who helped garner publicity for the issue of domestic abuse nationally, enabling many more refuges to be set up across the UK.

3. Oh Bondage! Up Yours!

Some people think little girls should be seen and not heard

But I thikn 'oh bondage, up yours'.

Poly Styrene, X-ray Specs, 1977.

Subculture provided opportunities for new models of womanhood from the 1970s. Punk, post-punk and alternative music scenes combined socially conscious, anti-authoritarian ideologies with DIY methods. Technnical virtuosity was out, and the amateur was in. Freed from the pressure of being the best, the first, or the most original, artists began translating the conventions of both high and popular culture, giving rise to new forms of expression.

Young musicians, artists, designers and writers set up bands, record labels, fanzines, collectives and club nights. They created work that pushed the boundaries of acceptability, often using clashing and violent imagery and explicit material. For many women this meant subverting gender norms, embracing the provocatively 'unfeminine' as well as the hypersexual.

Through their DIY methods, multi-disciplinary approaches and challenge to the status quo, these subcultures had much in common with the women's movement. Yet artist and post-punk musician Cosey Fanni Tutti notes: 'I aligned myself more with Gay Liberation than Women's Liberation... Freedom 'to be' was my thing. I didn't want another set of rules imposed on me by having to be a 'feminist''. For writer and punk feminist Lucy Whitman (then Lucy Toothpaste) it didn't matter whether these women identified as feminists or not, 'in all their lytics, in their clothing, in their attitudes - they were challenging conventional attitudes'. These artists were freeing women of the bondage of expectation and helping redefine women's role in society.

Caroline Coon, Between Parades, 1985, (oil on canvas)

Between Parades documents the experience of sex workers waiting for clients in a brothel.

Susan Swale, Hegemony, 1982

The marriage of Charles and Diana became a major point of discussion for feminists - they saw the exaggerated ceremony and archaic gender norms it represented as the antithesis of the lives they were fighting for. The title of Swale's work uses the term popularised by Gramsci.

Jill Posener

In these prints Posener documents a series of feminist interventions to advertising billboards around London. While living in lesbian squats in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Posener and her friends would graffiti over sexist adverts and photograph them. They sold prints as postcards to raise funds for radical causes. 'It was a way of taking over the poster. By writing angry but humorous graffitti, we were also making the point that ad agencies don't have the monopoly on wit', Posener writes.

4. Greenham Women are Everywhere:

On 5 September 1981, a group of women marched from Cardiff to the Royal Air Force base at Greenham in Berkshire. They called themselves Women for Life on Earth. They were challenging the decision to house 96 nuclear missles at the site. When their request for a debate was ignored, they set up camp. Others joined, creating a women-only space. Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp became a site of protest and home to thousands of women. Some stayed for months, others for years, and many (including a great number of artists in this exhibition) visited multiple times.

Greenham women saw their anti-nuclerar position as a feminist one. They understood that government spending on nuclear missiles meant less money for public services. They used their identities as mothers and carers to fight for the protection of future generations and a more equal society. The camp's way of life - communal living, no running water, regular evictions and arrests - was challenging. But Greenham was also a refuge. Women were liberated from the restrictions of heteronormative society and some embraced separatism. Race, class, sexuality and gender roles were regular topics of discussion.

Protest took on artistic forms for Greenham women. They made banners and collages, produced sculptures and newsletters, and weaved spider webs of wool around the perimeter fences. They wrote and sang protest songs and keened - wailing in grief to mourn lives lost to future nuclear wars. Large-scale public actions, like the 14-mile human chain created for 30,000 people holding hands to 'embrace the base' brought widespread media coverage to their cause.

Greenham politicised a generation of women, inspiring protests across the world, including the permanent peace camp at Faslane Naval base in Argyll and Bute. It also forged relationships and networks that continue to inform the women's movement.

'We can best help you prevent war not by repeating your words and following your methods but by finding new words and creating new methods'. Virginia Woolf.

Brides against the Bomb, (performance), photograph taken by Pam Isherwood)

Jacqueline Morreau, If Mary Came to Greenham, 1983 (oil on board)

Sam Ainsley, Warrior Woman V: The Artist, 1986

The Miners Strike:

Following WWI, there were 1 million miners in the UK. By the beginning of the 1980s, there were 200,000. In March 1984, the National Coal Board announced plans for a wave of pit closures. The National Union of Mine Workers led by Arthur Scargill, responded with a series of year-long strikes.

Observed across England, Scotland and Wales the strikes were a national issue. While all the miners were men, women played a vital role - setting up soup kitchens, campaigning and raising money. Their efforts were supported by their local communities, Greenham Common women and gay and lesbian activists. Determined to break the miners' union, Margaret Thatcher mobilised police forces. brought legal challenges and launched scathing attacks in the media. Many believed this crackdown on union activity coupled with the privatisation of industry put social democracy, civil liberty and the welfare state at risk.

On 3 March 1985, after 362 days and 11,291 arrests, the National Union of Miners voted to end the strike. The government made not a single concession.

In this section, some of the artists who defined black feminist art practice in the UK are highlighted. These women were part of the British Black Arts Movement, founded in the early 1980s. Their artworks explore the intersections of race, gender and sexuality. They do not share a unified aesthetic but acknowledge shared experiences of racism and discrimination.

Really great resource, thank you so much for uploading this :)

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment

ReplyDelete