UnNatural History

at the Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry.

In this exhibition international artists and naturalists explore the role of the artist as an intrinsic part of the science of natural history, enabling our modern understanding of ecology, climate change, extinction and threats to biodiversity. The observational skills and techniques of artists, including their speculations, have enabled the development of the biological sciences since their inception. We learnt about plants and animals through drawings long before the advancements of technologies such as microscopes and photography.

UnNatural History connects these natural history collections to the past, present and future of our relationship with nature.

This is a meticulous recreation of a stash of bird eggs collected by Matthew Gonshaw, one of Britain's most notorious egg thieves. In 2004, in one of several raids on his home, police found the eggs of a number of rare and endangered species hidden in his bed frame. Gonshaw subsequently became the first person to receive an ASBO for a wildlife crime. The eggs in the installation are hand-made porcelain replicas.

Yinka Shonibare, Butterfly Kid, 2019

The boy balances on one leg with his arms outstretched as if in flight. The butterfly motif is repeated in the pattern of his jacket and knickerbockers, which are cut in an old-fashioned style, suggesting Victorian costume. They are made with batik fabrics, which have rich multicultural associations and are a signature of Shonibare's work. Although connected to climate change the work is positive in tone, suggesting the possibility of metamorphic change and uplifting potential of beauty and growth.

Gerard Byrne, Eighth Beast, 2018 (analogue silver gelatin print)

Gerard Byrne, Second Beast, 2018 (analogue silver gelatin print)

The Beast series are photographs of a display at the Biologiska Museet in Stockholm. This natural history museum, founded in 1893, features a 360-degree diorama full of preserved foliage and taxidermied animals and birds to demonstrate the range of Sweden's biodiversity.

This display case includes school shoes worn by the artist's son between the ages of eight and eighteen, emphasising the passage of time. Displayed as a series they recall a collection of butterfly specimen.

Sarah Sze, Magenta Stone, 2013-15 (silkscreen on canvas, photographs of rock printed on Tyvek, aluminium)

Magenta Stone features actual rocks as well as the artist's sculptural and printed depictions of stones, playing on the process of observation and ideas of real and constructed nature. Sze has experimented with printing techniques to produce a trompe-l'oeil image of the rough surface of a rock. This motif is featured on the constructed rocks, and is also replicated in a single bright colourway on the canvas.

The work invites viewers to consider a single subject - a humble rock - that is once emblematic of nature and also a key material of human construction.

Tania Kovats, Badger,2021 (taxidermied badger)

Kovats' taxidermied roadkill animals invite us to consider our cultural attitudes and responses to death and extinction. Taxidermy has historically been used in natural history collections to preserve and present animals and birds that often come from other parts of the world and are seen as rare or exotic. The animals are usually portrayed in a lifelike state for the purpose of study or triumphant celebration. By contrast, Kovats has preserved animals that are common in Britain, and they have been stuffed in the positions in which they were found by the side of the road.

At first glance this bronze sculpture appears to be a straightforward representation of a foxglove plant. However, five of its petals are actually made from casts of the artist's fingertips. When she was a child, Cross was warned that if she put her fingers in a foxglove's bells and then licked them, she would go blind. The wild foxglove flower is the source of the drug digitalis, which is used for heart complaints. Ingestion of too much digitalis can impair vision, making one see only in blue and white.

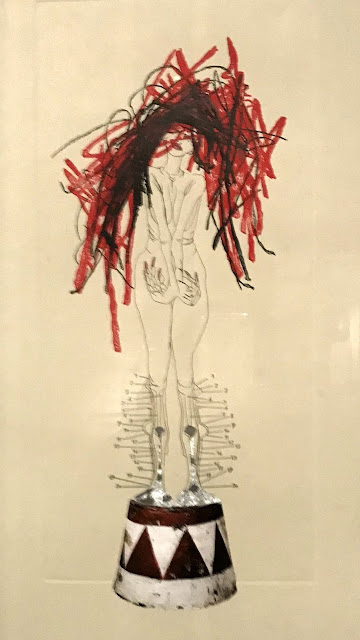

Wangechi Mutu, The Original Nine Daughters, 2012 (etchings with screenprinting, collage, letterpress, carbonundum crystals and hand-colouring on wove paper)

This series of prints celebrates the Nine Daughters of the Kenyan creation myth. According to Kikuyu beliefs, the first man and woman had nine daughters. When they were of marriageable age their father prayed for husbands for them. The following day nine men appeared under a sacred fig tree and wed the young women.

Their families became the ancestors of the nine Kikuyu clans. Mutu depicts the nine daughters as hybrid forms, some of which appear more futuristic than ancient. Many of the images incorporate references to Renaissance and Victorian etchings, including lettered and numbered pins that would have identified parts of the body. Others situate the daughters with natural phenomena including rocks and foliage. Despite these scientific allusions, Mutu intends the images to remain mysterious and esoteric.

No comments:

Post a Comment