at EMST (National Museum of Contemporary Art), Athens.

This exhibition is part of the What If Women Rule the World initiative at EMST. It was furthermore the second time this summer when I asked myself: 'why have I not heard of this artist before? Why have I not seen any of her work before?'

It was such a pleasure walking around the huge space in the basement where the exhibition is laid out, looking at everything. I have not included everything in this post. I have decided to write about Will in a separate post. I have not included any of her video work. I do not have the patience to watch videos but the one that is centred around Miki Theodorakis' Mounthausen I watched three times. It's just as well I was on my own in the viewing room because I howled while watching it. I can't remember having ever watched anything so moving and at the same time so well made. I might do something with it at a later date.

For 50 years Siopsis has explored the politics of the body, grief and shame as they play out in her home country, South Africa. In the process she has established herself as one of the most important voices of her generation on the African continent and beyond.

Born in South Africa in 1953 to Greek parents, Siopis came to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s with her historically and culturally charged paintings that are a fierce critique against colonialism, apartheid, racism and sexism. She went on to experiment with other media such as installation and film, creating a rich, incisive and poignant body of work that has consistently engaged with the persistence and fragility of memory; notions of truth and accountability; the rights of women and the disenfranchised; the issue of vulnerability; and the complex entanglements of personal and collective histories.

The History paintings:

Siopsis made her History Paintings in the mid-1980s to early 1990s, when the South African government clamped down on resistance to apartheid. These allegorical paintings comment on the situation through reference ot the grand tradition of European history painting. Their tilted perspective, heavy impasto and over-abundance of pictorial signs throws up history as a pile of debris set in a claustrophobic pictorial space laid waste by exploitation.

Melancholia, 1986, (oil on canvas)

Melacholia is a baroque allegory of colonialism in decline, a comment on white greed in the face of black dispossession under apartheid.looking closer

looking closer

Piling Wreckage upon Wreckage, 1989, (oil on canvas)

Piling Wreckage Upon Wreckage shows a young woman dwarfed by a flood of debris that lies before her, and to which she holds a cloth. It's title is taken from Walter Benjamin's Thesis on the Philosophy of History.

looking closer

Patience on a Monument: 'A History Painting', 1968, (oil on canvas)

Siopsis also referenced Benjamin's words on history in this painting Patience on a Monument: A History Painting, substituting 'he' with 'she'. 'Where we perceive a chain of events, she sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of her feet... The storm irresistibly propels her into the future to which her back is turned, while the pile of debris before her grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress'.

looking closer

looking closer

looking closer

Restless Republic: Groundswell, 2017, (newspaper cuttings, glue, ink and found object on canvas)

Over the last decade Siopis has combined found objects and texts from current newspapers in her process of painting with glue and ink.

In this work, cuttings from South African newspapers reporting on gender-based violence and femicide are shaped into an anti-monumental figure on a plinth. Phrases merge into each other but some are legible, such as 'Rise Up'. The texts are embedded in the glue, becoming cast in its organic and unruly patterns, some of which evoke the veins of a stone. An actual stone is wedged between the painting and the floor, calling to mind the phrase from resistance politics in South Africa, 'You strike a woman, you strike a rock'.Charmed Lives, 1998-99, (installation of found objects)

This work emerged out of Reconnaissance 1900-1997, a floor installation Siopis had created. The dates 1900-1997 in Reconnaissance reflect the idea that a person's memory covers a hundred years because one inherits the memories of people of no more than two to four generations who come before you. It was inspired by the artist having to pack up her mother's life possessions after an accident which resulted in her being moved into a managed care facility. What to keep and what to throw away; and the impossibility to contain life in categories. Those possessions included objects that came down from Siopis' grandmother carrying with them traces of time, of people's lives and of social histories spanning several generations and continents.Siopis has said, 'for me art seems always about the unfinished, the incomplete, the unsettled and the fragmentary. Charmed Lives is like an evergrowing, uncontrolled sort of encyclopedia of social and intimate relations. Some of its objects have been singled out to live in my forever unfinished Will work'. (there will be a post on Will).

looking closer

looking closer

looking closer

History Lesson, 1990, (pages from South African history books)

Pages from apartheid-era South African history textbooks are combined with a pictogram shaped by identical photographs of the artist as a child performing in a school concert. She appears to dance on the white male history that frames her.

Wringing Hands, 2002, (oil and acrylic on canvas)

Stranger, 2008, (glue and ink on paper)

Alongside her large canvases in glue and ink, Siopis worked with glue and ink on small paintings on paper, often in series. Here she draws on references from Greek antiquity and historical photographs to allude to how images of the past might help to look at the refugee situation in Greece.Cake Paintings:

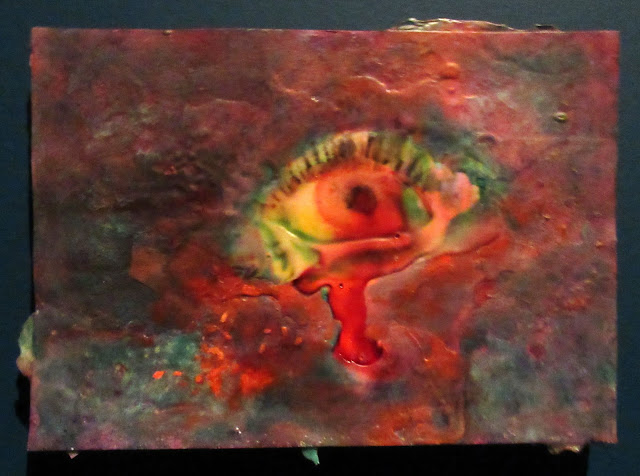

The Cake Paintings were her first major series. Here, oil paint became an object in its own right, and she associated the medium with flesh and skin. Using unorthodox tools, including cake icing implements, she modelled thick impasto surfaces into high relief. As she has said, 'as a child I'd watch my mother ice cakes, fascinated by how she transformed amorphous lumps of icing paste into things of beauty, gently guiding the material through decorative piping nozzles'.

The sexual morphology that emerged from the process calls into question traditions of the female nude linked to smooth surfaces and the possessive male gaze, as well as countering modernist values in (male) painting, with gender pushing through formalist flatness. Thick paint dramatically marks its own material change as it ages. The outside 'skin' dries long before the interior so the surface wrinkles and cracks.

Tapers, 1982, (oil and candles on canvas)

Column Cake, 1982, (oil and found objects on wooden base)

Embelishments, 1982, (oil and found objects on canvas)

'Experimenting with glue and ink over the years has been vital in working with material as a concept in painting; how the fiscous glue acts, how it changes from opaque to transparent when exposed to air, how it is affected by gravity when the canvas is placed horizontally on the floor, by the chemical make-up of ink and from my bodily gestures'.

In a very dark room, Warm Waters, 2018-2019, (installation/ 84 paintings)

The Warm Waters installation of small paintings on paper was made for a project about rising waters and migration across the Indian Ocean.

No comments:

Post a Comment