Kazimir Malevich at Tate Modern.

A visionary, a mystic, a revolutionary, an artist at the forefront of one of the most avant-garde movements in art of the 20th century. Born in Kiev, he lived and worked in Russia for most of his life and is considered a part of the Ukranian avant-guard but mainly as a Russian artist. Malevich was the first Russian artist who created wholly abstract compositions - his most famous work, Black Square became a universal symbol of a new era in art. He called his abstract compositions Suprematism, which in its first state meant the dominance of colour energy and its transformations in painting.

Exalting the 'heroism of modern life', Malevich wrote in 1915:

And I say:

That no torture-chambers of the academies will withstand the days to come.

Forms move and are born, and we are forever making new discoveries.

And what we discover must not be concealed.

And it is absurd to force our age into the old forms of a bygone age.

The void of the past cannot contain the gigantic constructions and movements of our life.

With Suprematism he strove towards a pure, geometrical abstraction which represented a final disengagement of painting from reality and marked its entry into the exalted realm of pure thought - an escape from painting's depictive role.

Many phenomena that appeared for the first time in his work were only picked up on years later. The simple, singular shapes of his Suprematist paintings are harbingers of the aesthetics of minimalism in the second half of the 20th century. One of his drawings that was made public in 2000 shows the word 'village' in a frame: 'instead of drawing the huts of nature's nooks, better to write 'village' and it will appear to each with finer details and the sweep of an entire village', he wrote. This is what conceptualists did many years later. Finally, in his first exhibition, Kazimir Malevich: His Path from Impressionism to Suprematism, following the white on white works, the exhibition ended with empty canvases that invited the viewer to project her/his own ideas. In 1924 in one of his notebooks the line 'the goal of music is silence' appeared - an idea that was realised by John Cage in 1952 when he created his opus silent 4'33.

Early painting:

During the early years, influenced by Monet and Cezanne, he painted his own impressionist scenes, but also began to consider the work of art as an independent creation rather than a mere imitation of reality.

Self-Portrait, 1908-10

Bathers Seen from Behind, 1910

Bather, 1911

A Russian Artist

Alongside other painters such as Natalya Goncharova, Malevich aspired to develop a uniquely Russian form of modernism fusing innovations of the western avant-garde with the simplified forms and expressive colours of popular Russian prints and icons. He particularly focused on the image of the peasant, regarded as the embodiment of the national soul.

The Scyther, 1911-12

The Floor Polishers, 1911-12

Peasant with Buckets, 1912

Cubo-Futurism

Filippo Marinetti who published the 'Futurist Manifesto' urged artists to reject the past in favour of speed, technology and the cult of the machine. His influence was felt across Europe, but the Russians developed a hybrid form of painting called Cubo-Futurism which combined the dynamism and movement associated with Italian Futurists with the fractured perspectives of cubists such as Picasso and Braque. Malevich applied this style to rural scenes and combined it with the bold colours of traditional Russian art rather than the muted tones favoured by Cubists in Paris.

The Woodcutter, 1912

Samovar, 1913

Life at the Grand Hotel

Morning in the Village after Snowstorm, 1912

Painting, Poetry and Theatre

Malevich, the musician Mikhail Matyushin and the poet Aleksei Kruchenykh collaborated on a manifesto calling for the dissolution of language and the rejection of rational thought. They staged a futurist opera, Victory over the Sun in St Petersburg in 1913. Malevich designed the costumes and backdrops which were dominated by geometric areas of colour. The idea of words without meaning encouraged him to abandon pictorial conventions to conceive what he called alogical painting. This allowed colours and forms to sever their ties to the physical world. In 1914 Malevich declared his renunciation of reason.

During the same time, Olga Razanova displayed a similar degree of radical innovation in her collages.

Olga Razanova, Non-Objective Composition, 1915

Olga Razanova, Non-Objective Composition, 1915

An Englishman in Moscow, 1914

Toilet Casket, 1913

Station Without a Stop, Kuntsevo, 1913

Sketch for coctume for Victory Over the Sun, 1913

Sketch for coctume for Victory Over the Sun, 1913

A modern icon

Black and White, Suprematist Composition, 1915

Black Square, 1923

This painting was the starting point for a wholly new approach to art - Suprematism which is all about the supremacy of colour in painting. Malevich took geometric shapes and a limited palette of colours and created a specific focus on the painted form and colour, existing on the canvas purely as paint, not representing landscape, an object or a person. 'Up until now there were no attempts at painting as such without any attribute of real life. Painting was the aesthetic side of a thing, but never was original and an end in itself', he noted in The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.01.

Wanting to completely abandon depicting reality and instead invent a new world of shapes and forms that belonged exclusively in the realm of art for art's sake, he wrote in his 1927 book The Non-Objective World: 'In the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square'.

The surface of the original painting soon began to crack and Malevich painted another version around 1923. He painted four versions in all.

The Black Square became his motif, even his logo or trademark. Even in his later work, when he made a return to figurative paintings he signed many of them with a little black square. At his funeral the car carrying his body had a black square on the front, mourners held flags decorated with black square, and a black square went on to mark his grave. It became not only an icon of his style, but an icon of 20th century art. This is the first and last word in abstraction painting's absolute zero.

The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10

Having defined the precepts of Suprematism, in December 1915, Malevich unveiled 39 works at the group exhibition The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10 held in Petrograd. A single photograph survives to show the layout of Malevich's paintings; nine of the twelve paintings were shown at the Tate, displayed as in the original exhibition. Black Square was placed high up on the wall across the corner of the room, the sacred spot that a Russian Orthodox icon of a saint would sit in a traditional Russian home. He wanted to show the Black Square to be of a special or spiritual significance, make it the star of the show and the overriding emblem of his new style.

Suprematism: Self-Portrait in Two Dimensions, 1915

Red Square, (Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions), 1915

Painterly realism of a Boy with a Knapsack - Colour Masses in the 4th Dimension, 1915

Suprematism and Colour

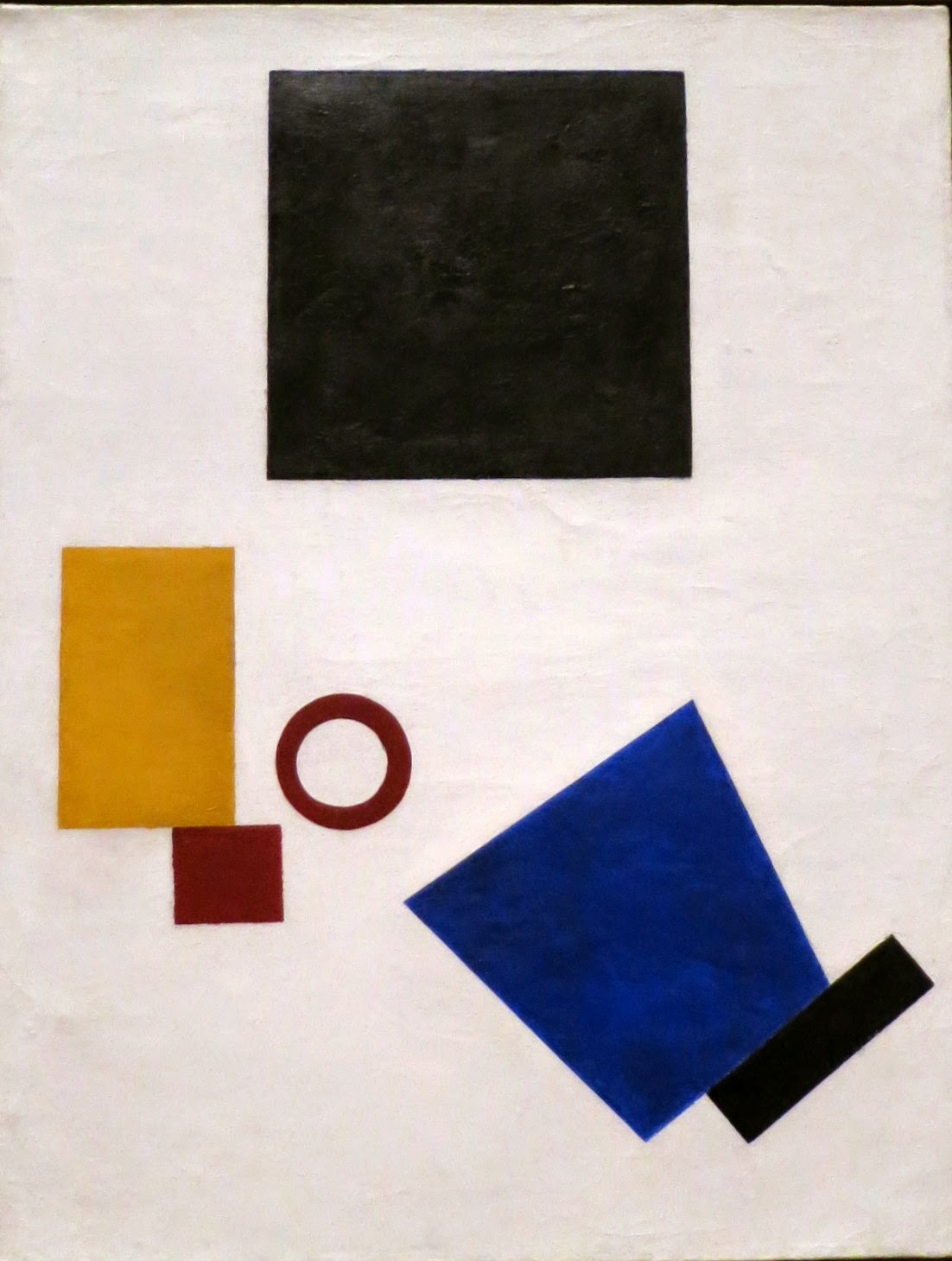

In his booklet Cubism, Futurism and Suprematism, Malevich argued that 'the artist can be a creator when the forms in [his] pictures have nothing in common with nature... Suprematism is the beginning of a new culture... Our world of art has become new, non-objective, pure. Everything has disappeared, a mass of material is left from which a new form will be built'. At the heart of Suprematism was colour, harnessed into geometric forms.

Supremus No. 50, 1915

Suprematism, 1915

Suprematist Painting, 1916

The End of Painting

The October Revolution was greeted by artists enthusiastically: they saw the political transformation of society as a parallel to their own radical transformation of art. Yet there was also an intense questioning of the purpose of art in an egalitarian new society.

During that time Malevich enacted a gradual dissolution of painting before abandoning it altogether. Simpler forms and single planes of colour that seem to soften at the edges followed. In some works colour fades away entirely. White forms against a white background represented a final liberation from the world of visible forms. 'Painting died like the old regime, because it was an organic part of it', he wrote in 1919.

White Suprematist Cross, 1920-21

Architecton Gota, 1923 (image taken from here)

He started designing Architectons, Utopian structures of no clear purpose, somewhere between Magic Mountain and New York skyscraper, which he envisaged as components of dream cities of the future.

Reinventing Figuration:

A few years after the October Revolution, Malevich abandoned painting for teaching and writing and by the time he picked up a paintbrush again in the late 1920s (having applied unsuccessfully for political asylum in Poland), his revolutionary abstractions were now deemed elitist and unacceptable by the Stalinist regime. Yet while Malevich's late subject matter found him reverting to figurative landscapes and blank-faced, robotic peasants, he always made a point of signing even these more conventional works with a small black square.

Female Torso, 1928-29

Sportsmen, 1930-31

Harvesting, 1928-29

Head of a Peasant, 1928-29

Three Female Figures, early 1930s

Portraits

In the 1930s, accused of spying for the Germans, interrogated and imprisoned, he completed a series of painfully retrogressive portraits inspired by Renaissance masters. The black square is still there, hidden in the backgrounds of the paintings, the final mark of defiance. I found this room extremely depressing. Totalitarianism had triumphed. This was the end of creativity. I could not bear to look and took no photographs, save for the one below.

Woman Worker, 1933

Sources:

Tate booklet

The Cosmos and the Canvas: Aleksandra Shatskikh.

Hi was, is and will be UKRAINIAN artist

ReplyDelete*He

DeleteYou are right, and I have changed the post accordingly. Malevich is usually referred to as a Russian artist, and this is why I made the mistake I made. I totally understand your frustration though.

Delete"Malevich aspired to develop a uniquely Russian form of modernism fusing innovations of the western avant-garde with the simplified forms and expressive colours of popular Russian prints and icons. He particularly focused on the image of the peasant, regarded as the embodiment of the national soul"

ReplyDeleteI know this article is from 10 years ago but it is incredibly saddening how Malevych could literally focus on the image of a Ukrainian peasant, while also identifying himself as a Ukrainian AND having Polish ancestry, yet still the word "russian" is used repeatedly and insistently to describe his works. There indeed was a huge impact of the russian art space and movements but it is just the consequences of the colonial nature of russia, aimed to erase and steal. His works about Holodomor are particularly heartbreaking.

I totally agree with you. He, and so many others, are not Russian, yet they are referred to as such. I went to an exhibition recently where even though the title was 'Russian Art', when they described each art work, they did mention the actual country of origin. It was so refreshing. Thank you for your comment

ReplyDelete