'Plato speaks of an artist turning the invisible world into the visible. I hope that someone seeing my sculpture is lifted out of his ordinary state'.

Takis,

at Tate Modern.

Panayiotis Vassilakis - known by the nickname Takis - became one of the most original artistic voices in Europe in the 1960s. He remains a ground-breaking artist today. This exhibition includes work from across his 70-year career.

The exhibition is arranged by themes that shaped Takis' creative universe: magnetism and metal, light and darkness, sound and silence.

This was a sensory experience: photographs, and consequently this blog, cannot do it justice.

Iocasta, 1954, (iron)

Oedipus and Antigone, 1953, (iron and wood)

Magnetism and Metal:

In 1959, Takis made a leap from figurative art to a new form of abstraction, based on magnetic energy. He suspended metal objects in space using magnets, giving lightness and movement to what is usually gravity-bound and still. He was fascinated by the waves of invisible energy that he saw as 'as a communication' between materials. Art critic Alain Jouffroy described these works as 'telemagnetic'. 'Tele' meaning 'at a distance', suggests their relationship to technologies such as television and the telephone.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s Takis incorporated radar, antennae, aerials, dials and gauges into his sculptures. Although he approached these materials with knowledge about engineering and science, he consistently defined himself as an artist geared towards mythological thought. In his hands, technologies of warfare and environmental destruction became monuments of beauty and contemplation 'My desire as a sculptor was to learn to use this energy, and though it, to attempt to penetrate cosmic mysteries', he explained.

He produced various 'telemagnetic' installations in the early 1960s using plinths, walls and the ceiling of the gallery. The installations challenged the traditional conventions of sculpture. Waves of magnetic energy move through these spaces, holding the individual elements in suspension.

Magnetic Fields, 1969, (metal, magnets, wire)

A large grouping of flower-like sculptures are brought to life by the magnetic pendulums that swing overhead.

Early in his career, Takis began experimenting with how to use energy and movement in sculpture. 'What interested me was to put into iron sculpture a new, continuous and live force'... The result was in no way a graphic representation of a force but the force itself. Marcel Duchamp described Takis as the 'happy ploughman of the magnetic fields'.

Magnetic Wall (Flying Fields), 1963, (cork, cloth, magnets, metal, metal wire, wood)

Electro-Magnetic Music, 1966, (amplifier, electromagnet, magnet, metal wire, needle, paint, spark plugs and wood)

Musicals, 1985-2004, (electromagnets, iron, metal string, nylon thread, paint, steel needles, wood)

Like many of the works in this exhibition, this work is on a timer. It runs for approx. 5 minutes followed by a rest of 5 minutes. Electromagnetic forces used in the work give it a life of its own.

'My intention was to make nature's phenomena emerge from my work... in nature everything is sound: the wind, the sea, the humming of insects'.

Takis' sculptures produce sounds ranging from single notes to thunderous ensembles. They respond to surrounding air currents, generating delicate noises. Magnets pull metal rods against instrument strings to produce what he called 'space sounds'.

Magnetic Wall 9 (Red), 1961, (acrylic paint on canvas, copper wire, foam, magnets, paint, plastic, steel, synthetic cloth)

Takis began his Magnetic Walls series in 1961. Magnets are hidden behind the canvas of these single-colour paintings. Hanging metal objects are attracted to these magnets, hovering just above the canvas surface. The result is an expansion of painting, where abstract elements, instead of being painted on the canvas, float in space over it. Takis spoke of his work as creating an 'action in space', rather than the 'illusion of space' that many previous artists had achieved.

Telepainting, 1959, (acrylic paint on canvas, magnets, nylon thread, steel)

Takis began to use electrical lights in his work in the early 1960s. His inspiration came after waiting for hours at a train station en route to Paris from London. He described the station as a forest of signals: 'monster eyes' flashed on and off in a 'jungle of iron'.

Takis found many of his materials in military surplus stores selling supplies left over from WWII.

Telelumiere Relief No. 5, 1963-64, (electrical components, lightbulbs and wood)

Activism and Experimentation:

Social and political activism hold a central place in Takis' life and practice. In 1968, he was of the first visiting fellows at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the USA. There he continued to produce works using electromagnetism. He also developed work harnessing renewable energies in conjunction with scientists and engineers. Takis described these collaborators as 'poets' and 'creators'. His residency resulted in a patented device for transforming water currents into electricity. In an effort to democratise art, he also collabotated with engineers in London to produce affordable, mass-produced editions of his sculptures.

In 1969, while living in New York, he physically removed his work from an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. It had been exhibited against his wishes. This action led to the formation of the Art Workers' Coalition. It included artists, filmmakers, writers, critics and museum staff. The coalition advocated for museum reform including a less exclusionary exhibition policy in relation to women artists and artists of colour.

Triple Signal, 1976, (bronze, found objects, iron)

Triple Signal, 1976, (bronze, found objects, iron)

Takis' Signals resemble radio receivers. For him, they are 'like electronic antenna, like lightning rods... They constituted a modern hieroglyphic language...'

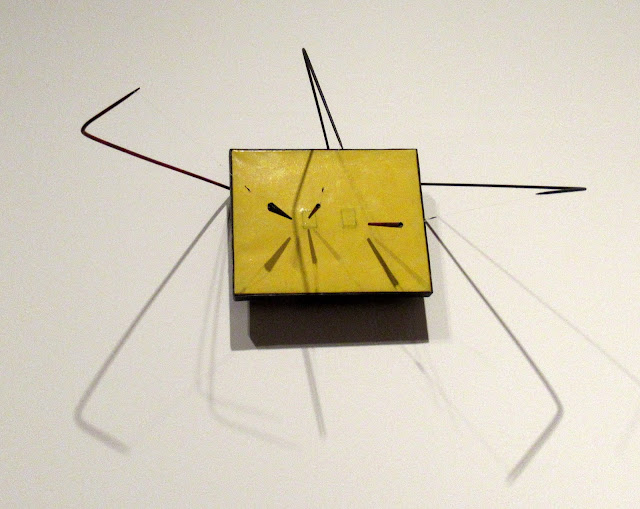

Insect, 1956, (acrylic sheet, bronze, paint, steel)

Triple Signal, 1976, (bronze, found objects, iron)

Takis' Signals sculptures from the 1970s include bomb fragments from the Greek Civil War. They were gathered from the hillside around his Athens studio. The use of these materials transforms the remnants of war into monuments of beauty and contemplation. Formed by an explosion, the bomb fragments also relate to his fascination with all manifestations of energy, from the subtle to the dramatic. 'Sometimes I explode materials in order to increase the flow of energy and observe the effect'.

Musical Sphere, Electromagnetic Sphere and Gong

Gong, 1978

No comments:

Post a Comment